We commissioned Frontier Economics to evaluate the economic impact of trust in data ecosystems. Below, you can read the foreword from Open Data Institute (ODI)’s Vice President and Chief Strategy Advisor Jeni Tennison, and an abridged version of the report. The full report is also linked below.

Foreword

Data flows can create value for our societies in a myriad of ways: when data is made open or shared, it enables better decisions, more effective policies, more innovative and useful services, and generally can make our lives better, while fueling economic growth and productivity. Some of this value creation can be measured in monetary terms, while in other ways it is almost intangible. Researching and documenting this rich variety of value creation has been at the heart of the work of the ODI, from our 2015 report ‘Open data means business’, to our recent collaboration with the Bennett Institute for Public Policy.

We also know from countless examples that data can cause harms, and that trust and trustworthiness is a key to enabling this creation of value. Fear of harms caused by the use and misuse of data can lead people to opt out of data collection or avoid using services; organisations may avoid collecting, using or sharing data to avoid risks.

One part of the equation has until now been elusive: can we quantify the importance of trust on the potential value of data? Can we get a better sense of how much trust – or lack thereof – impacts the value created by data flows?

This is a hard question to answer: trust is complex, and so is its impact on the value of data. But it is a question worth exploring: understanding the economic value of trust in data ecosystems would help policymakers and companies justify investment in activities that assess, build, and demonstrate trust and trustworthiness.

We are therefore delighted to introduce this work by economics consultancy Frontier Economics, commissioned by the ODI as part of the Innovate UK-funded Data innovation for the UK: research and development programme, and which took on the challenge to explore this topic with us, rigorously reviewing existing evidence and proposing an economic model of the impact of trust on data ecosystems.

— Jeni Tennison, Vice President and Chief Strategy Advisor, ODI.

The economic impact of trust in data ecosystems – summary report

Introduction

Data is abundant in the modern world, and many emerging technologies and their ecosystems rely heavily on high-quality information. If used effectively, data can drive productivity, boost innovation, and increase inclusion. However, data is not always held by the party that could realise these benefits, and data sharing that would increase societal benefits does not always happen.

Trust is important in this context, and it needs to be created and maintained between the parties who share, collect and use the data. Mistrust between these groups reduces the potential positive economic and social value that can be generated.

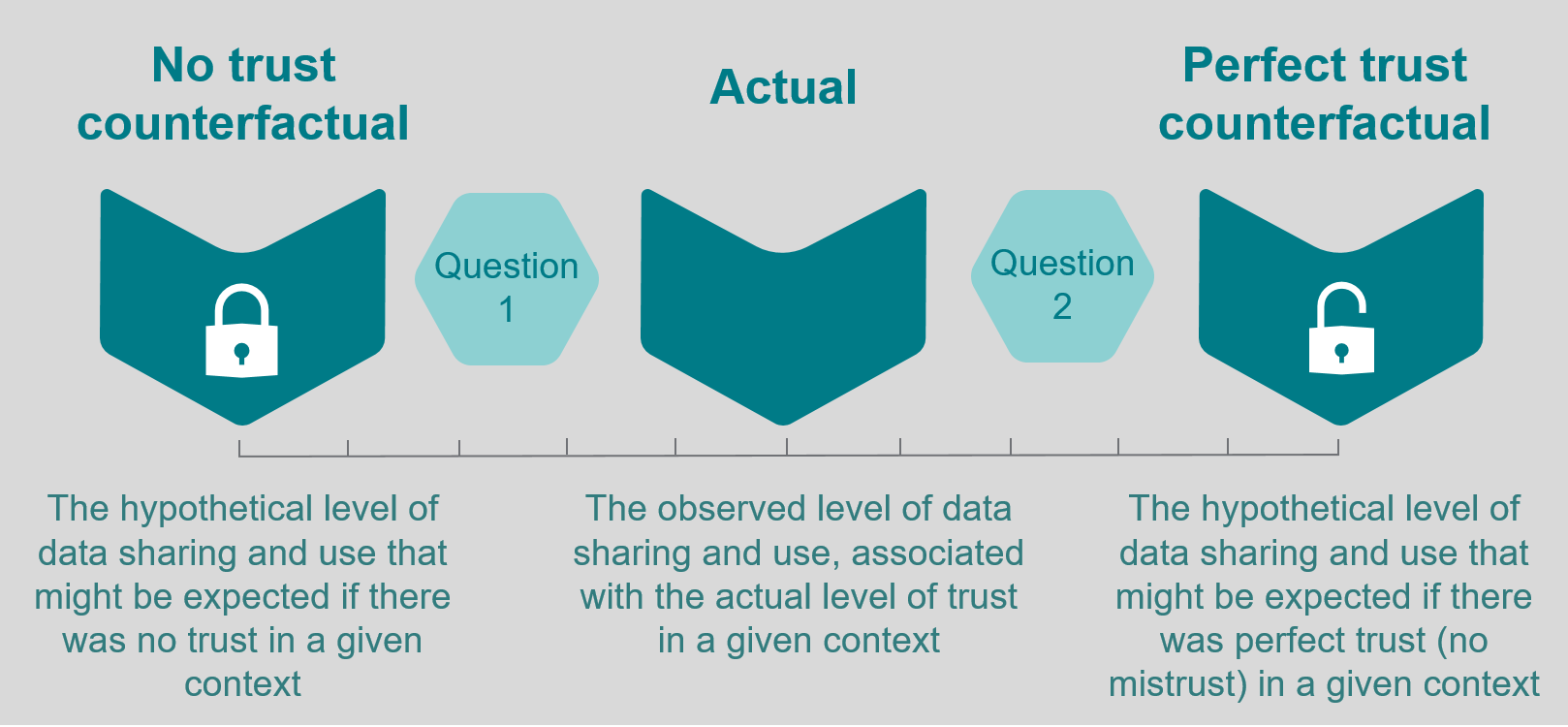

The ODI commissioned Frontier Economics to conduct an evaluation of the economic impact of trust in data ecosystems. In particular, we examined (Figure 1) the impact of trust on data sharing, collection and use within a data ecosystem. We also explored the economic value that can be attributed to the impact of trust on data sharing and collection in data ecosystems. Our work addressed an important gap in the current evidence base and complemented ongoing research that explores which mechanisms can be used to improve trust between organisations, individuals and other parties around data.

Figure 1: Our study's research questions

Note on language

This report considers relationships of trust and trustworthiness in complex ecosystems. For simplicity, whenever referring to organisations, individuals and other parties acting within a data sharing ecosystem, the term 'actors' was used.

Our economic framework

Existing studies have broken trust down into key components such as ‘credibility’ ‘reliability’ and ‘competence’. For example, Gupta and Dhami in ‘Measuring the impact of security, trust and privacy in information sharing: A study on social networking sites’ (2015) define trust as: ‘willingness of a party to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action’.

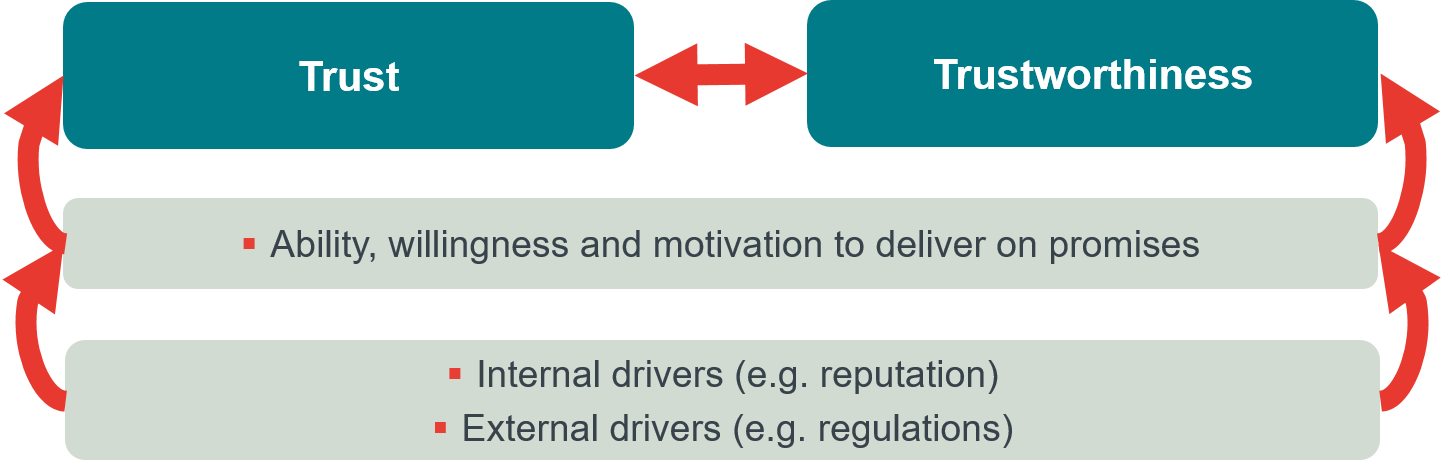

We have built on previous work from the ODI which has made a distinction between trust and trustworthiness. Being trustworthy is different from being trusted, and the two must be aligned to avoid a breakdown of trust. We have presented a visual summary of this in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Defining Trust

Trustworthiness is often a precondition to building trust. However, it can also be the case that some elements of trust are needed for an organisation or individual to build their trustworthiness. An actor’s trustworthiness can be measured along multiple dimensions, including its ability, willingness and motivation to deliver on its promises. These dimensions typically depend on context and are influenced by several drivers (eg reputation, laws, regulations, social or economic norms). In turn, trust can be driven by a range of factors. For example, when sharing data these include perceived security and privacy. When sharing and using data, factors such as the perceptions of how useful the purpose of that behaviour is, may influence trust.

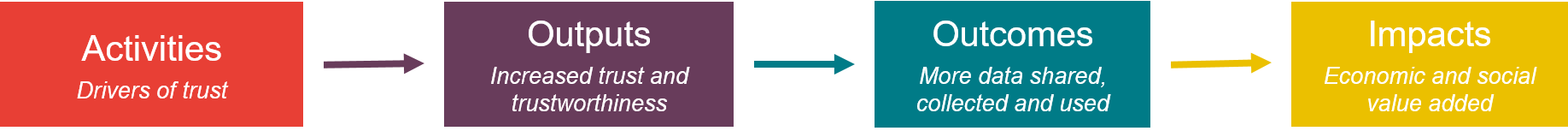

Trust can be linked to data sharing, and ultimately to the economic impact of that data sharing, using a logic model framework. This is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Impact of trust logic model

Our logic model describes how activities including laws, regulations, norms and standards, facilitate an environment with a high degree of trust and trustworthiness. The direct output of these activities is that trust relationships between the actors of a data ecosystem are strengthened. A virtuous cycle of increased trustworthiness and trust enables an outcome of data flowing more freely within the ecosystem. This cycle results in more data being collected, shared and used. Greater data usage generates economic and social impacts as a result of better commercial and public sector decision making, increased competition and increased innovation.

Greater use and collection of data, in part facilitated by greater trust, can also generate benefits associated with evidence-based policymaking. As a result, society at large benefits from a more trustworthy data ecosystem in both the public and the private sphere.

A static view of the relationship between trust and data sharing

Following an extensive ‘literature review’ we combined results from seven academic studies. They were chosen because they included quantified estimates of the impact of trust on data sharing. Our work examined whether trust had an impact on whether organisations and individuals were more likely to share data. We however found a higher volume of evidence on the impact on individuals, and less for organisations. Nonetheless, our results tentatively suggest there is currently no strong reason to expect any difference in the impact of organisational versus individual trust on data sharing.

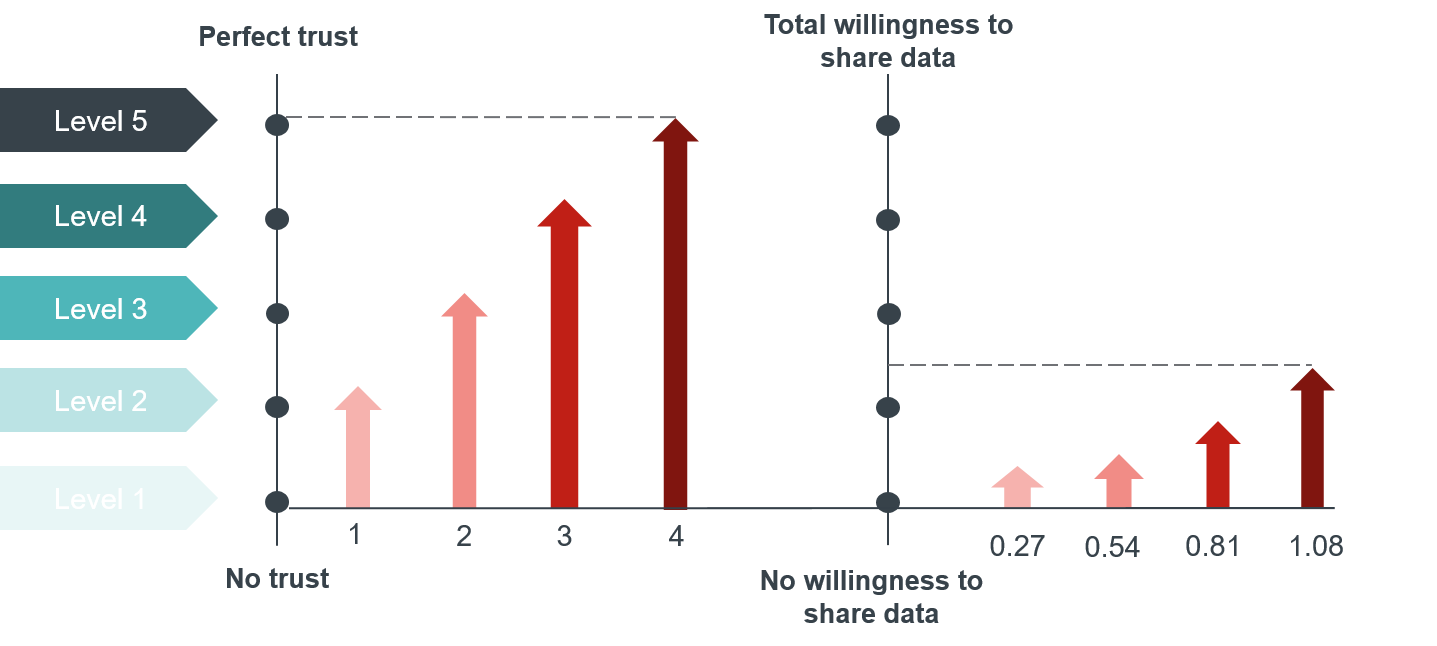

Our calibration of existing survey evidence revealed that, on average, a 1 point increase on a 5 point trust scale leads to a 0.27 point increase on a 5 point data sharing scale. (This effect does not refer to any specific baseline levels of trust and data sharing.)

Larger jumps in trust could correspond to bigger impacts on data sharing. For example, a 4 point increase on a 5 point trust scale could lead to a 1.08 increase on a 5 point data sharing scale (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average impact of trust on data sharing

These aggregate results show that even large increases in trust will only correspond to moderate impacts on willingness to share data overall. This serves to emphasise that there are many factors, alongside trust, which cause data sharing to be lower than optimum. Increasing trust without addressing these other factors is unlikely to be sufficient.

For example, to reach optimal levels of data sharing, the wider context and data sharing infrastructure would need to be improved, and ways of accessing and assessing data sharing, would have to be addressed. On top of this - the evidence around trust in data we have used to model our results measures willingness to share data, rather than actual data sharing in practice. It may be that our estimates are conservative, and once a certain average level of willingness to share data is reached, actual data sharing rises by a greater amount.

Linking these estimates to the available academic and policy literature about the social and economic impact of data access and sharing, allows us to estimate the order of magnitude of the economic impact of trust in data ecosystems. Overall, the evidence we have reviewed suggests that data sharing can help generate social and economic benefits worth between 0.1% and 1.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the case of public-sector data, and between 1% and 2.5% of GDP when public-sector and private-sector data are combined. If we scale this up to the GDP of the 20 largest economies in 2019, estimates suggest that data sharing could unlock between $700bn and $1.75tn in value.

Linking these wider results to our framework suggests that a 25% increase in data sharing could therefore generate an additional $47.3bn to $118.3bn worldwide. It is worth noting that most of the studies which examine the economic value of data sharing focus on organisations sharing and re-sharing data (rather than individual data sharing). This does lead to some additional uncertainty, as the majority of our quantified evidence on the impact of trust on data sharing is at the individual level.

We also explored the circumstances in which trust is likely to have a larger or smaller effect on ‘data flows’.

Baseline levels of trust

The impact of trust tends to be larger in situations where initial levels of trust are low, compared to when there is already a significant amount of trust between actors in the ecosystem. This finding is based on a small subset of academic papers that report baseline levels of trust.

This also matches our qualitative engagement. Stakeholders confirmed that baseline levels of trust matter. For example, organisations active in the healthcare data ecosystem confirmed that intervening quickly to address concerns is vital to facilitate data sharing when trust levels are low. In these cases, the benefits of sharing data has yet to be articulated to all stakeholders in a compelling way. Therefore, allowing uncertainty to persist can quickly lead to a significant loss of willingness to share data.

Where trust is high, we were told that other stakeholders will be more likely to give ‘data institutions’ the benefit of the doubt and need a relatively compelling reason to stop sharing data. Other stakeholders noted that in newer ecosystems, where baseline levels of trust are relatively low, there is greater emphasis placed on formal regulations and rules, as trust based on the development of relationships over time has not yet materialised.

Importance of context

The impact of trust can vary based on the context of a specific ecosystem. The studies we have used cover a range of different sectors, geographies and data ecosystems. We can be confident that the impact estimates linked to each of these studies will in part depend on the contexts and ecosystems in which they were carried out. Our qualitative engagement, where we asked stakeholders to describe their experiences, confirmed that contextual factors are crucial to understanding the role of trust in influencing data sharing. For example, all stakeholders agreed that sharing more sensitive forms of data would require higher levels of trust and perceived security in advance. How common these different and more sensitive types of data are, will vary depending on the ecosystem or sector in question Also, norms and unwritten attitudes will play a role in determining baseline levels of trust. These norms are likely to vary substantially both between individuals and also across different regions. Importantly, interviewees emphasised that while different ecosystems are unique, efforts should be made to exhibit and build trust in data sharing horizontally, across all sectors, rather than purely on a sector-by-sector basis. This is because certain data ecosystems cannot be treated in isolation, particularly from the point of view of end users. To achieve this level of consistency while still accounting for differences in context may involve setting out general principles and/or categories of intervention to build trust. These can then be adapted and tailored for flexible implementation in different sectors and scenarios.

Dynamic effects of trust

We examined a set of major shocks to trust in real-life settings (ie ‘natural experiments’), by selecting instances where trust was eroded or where regulations were introduced to increase trust. These examples enable us to capture the impact of an external (and, in some cases unanticipated) change in trust on actual data sharing behaviour and get closer to identifying a causal relationship between trust and data sharing.

We analysed the impact of trust in these examples within the theoretical framework shown below, which defines two 'counterfactual scenarios' ie hypothetical situations that take into account what would have been the result if events had happened in a different way, in this case in the opposite way (Figure 5):

Figure 5: Movements in trust

As expected, in all cases analysed, a breach in trust caused reputational damage to the data institution as well as a decrease in the number of individuals willing to share data with that particular institution. This is consistent with our parameterised trust model (Figure 3), that places the idea of the impact of trust within a data ecosystem within clearly defined limits.

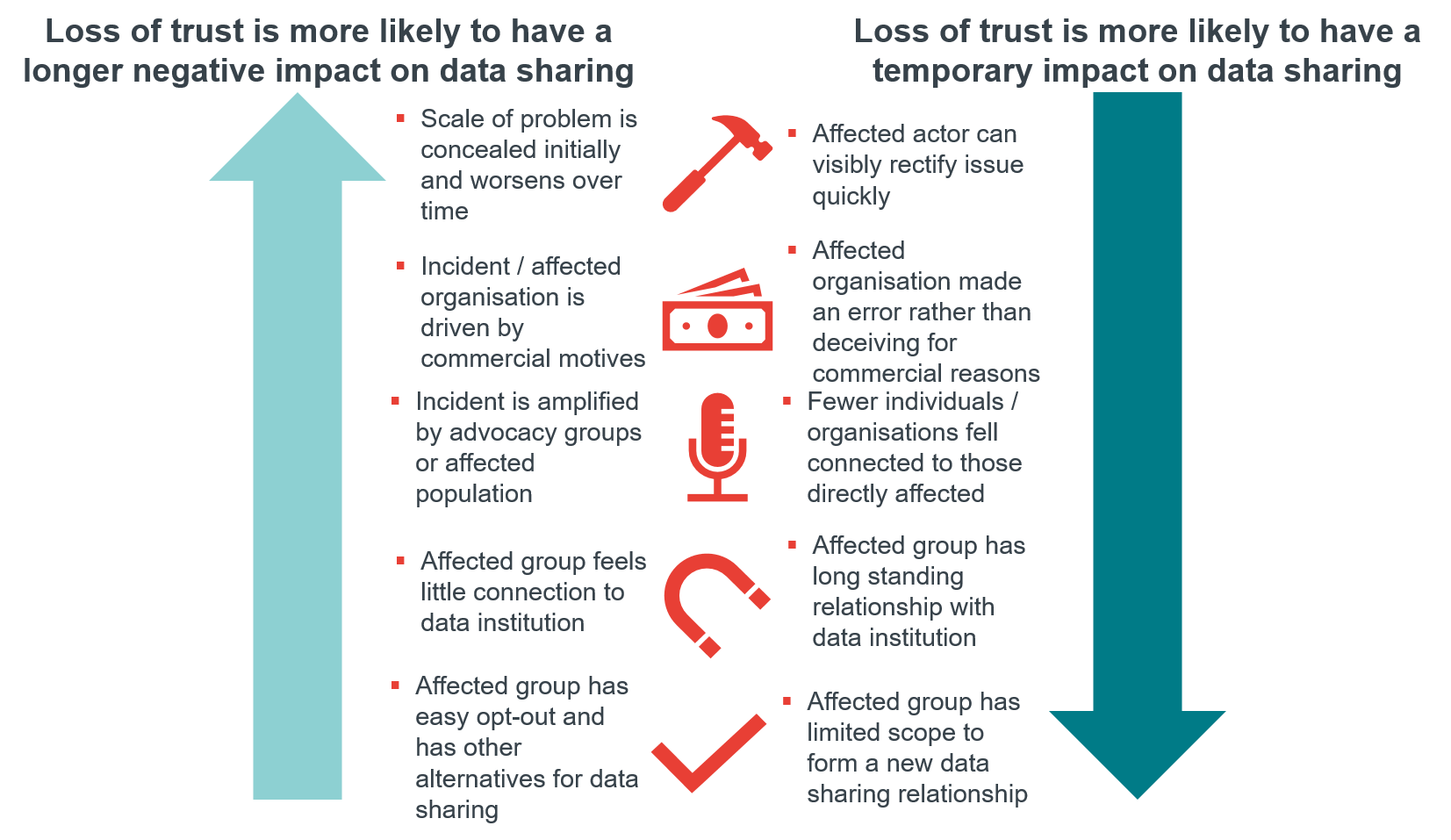

In some cases, the ‘negative shock’ to trust had a permanent impact whereas in other cases, the reduction in data sharing was temporary. We explored the prolonged impact of shocks to trust as part of our qualitative engagement. Stakeholders highlighted a number of factors which could lead to a bigger and longer lasting impact following an initial loss of trust (Figure 6).

The policy interventions we examined focused on designing a set of rules that ‘data intermediaries’ can conform to, to increase their trustworthiness. For example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a regulation which seeks to increase trustworthiness of organisations handling personal data. Evidence suggests that the effects of the GDPR might be non-linear over time. Interventions such as GDPR might pose an additional burden on institutions managing data in the short term, therefore initially deterring data sharing in the ecosystem. In the medium term, as data intermediaries become more comfortable with the regulation and prove their trustworthiness to data contributors, data flows may gradually increase, and could overtake pre-intervention levels.

Figure 6: Factors influencing persistence of negative trust shocks

Interviewees noted that these types of intervention can be beneficial. However, we were told that attributing an impact on data sharing to a specific intervention is difficult. In a few cases, we were told that new regulations force actors to share data with organisations who they do not necessarily trust. This clearly reduces the number of ‘trust interactions’ required. However, we were told that without having this choice, data providers feel as though trust is no longer a relevant concept. In order to mitigate these concerns, rules and regulations created before the event are needed, along with clear information on the sanctions that will be applied and the redress mechanisms that will be enforced if they are not.

Key takeaways and suggestions for future research

There is robust quantified evidence that greater trust is associated with increased data sharing. This confirms existing anecdotal evidence and justifies ongoing efforts to design mechanisms to boost trust. In cases where there is scope to achieve significant improvements in trust, the relevant effect size will be large.

However, the average magnitude of the relationship between trust and data sharing suggests that boosting trust will have to be accompanied by a suite of other interventions (enabling greater discoverability of data, for example) in order for data sharing to reach its optimal level. Exploring wider factors impacting data sharing and how they can complement increases in trust will be an important area for future research. Context is also extremely important in determining the impact of changes in trust. The specific ‘trust linkages’ that exist and their maturity matter, and will vary across (and within) certain sectors.

Whilst there is some causal evidence on the impact of trust, only a relatively small set of academic papers quantifies the actual impact of trust on data sharing. The majority of these papers tend to focus on individuals sharing data about themselves. The majority of studies have also been carried out recently, which highlights this area as an active branch of research, and one which would benefit from continued research.

Our research also identified key gaps in the existing evidence which make it challenging to link our core findings, on the impact of trust on data sharing, to the wider literature, on the economic impact of data sharing, collection and use. Firstly, while there is some quantified evidence on the impact of trust on data sharing by individuals, there is comparatively less on the impact of trust on data sharing between organisations. Secondly, and conversely, the majority of the evidence which assesses the impact of data sharing on economic outcomes is focused on organisational data sharing as opposed to data sharing

Read the full report here: