We are exploring the concept of 'digital twins', and how this can be applied to the built environment to inform decision making – and are also working with Digital Framework Task Group to support the creation of a 'national digital twin'

A ‘digital twin’ is a digital model of a physical object. While the term was coined in 2002, the concept of a ‘digital twin’ has been around for years – from simulating the conditions in the Apollo 13 spacecraft in 1970, to current use in manufacturing, the automotive industry and healthcare.

We are exploring the concept of digital twins in the context of the built environment. A digital twin can be used to monitor physical infrastructure in real time or to simulate problems or future scenarios. This could be a model of how traffic flows down motorways, or how a bridge responds to loading and usages. These digital models are driven by data, sometimes supplied in real-time, and the insights generated by this data are used to make decisions about the physical twin.

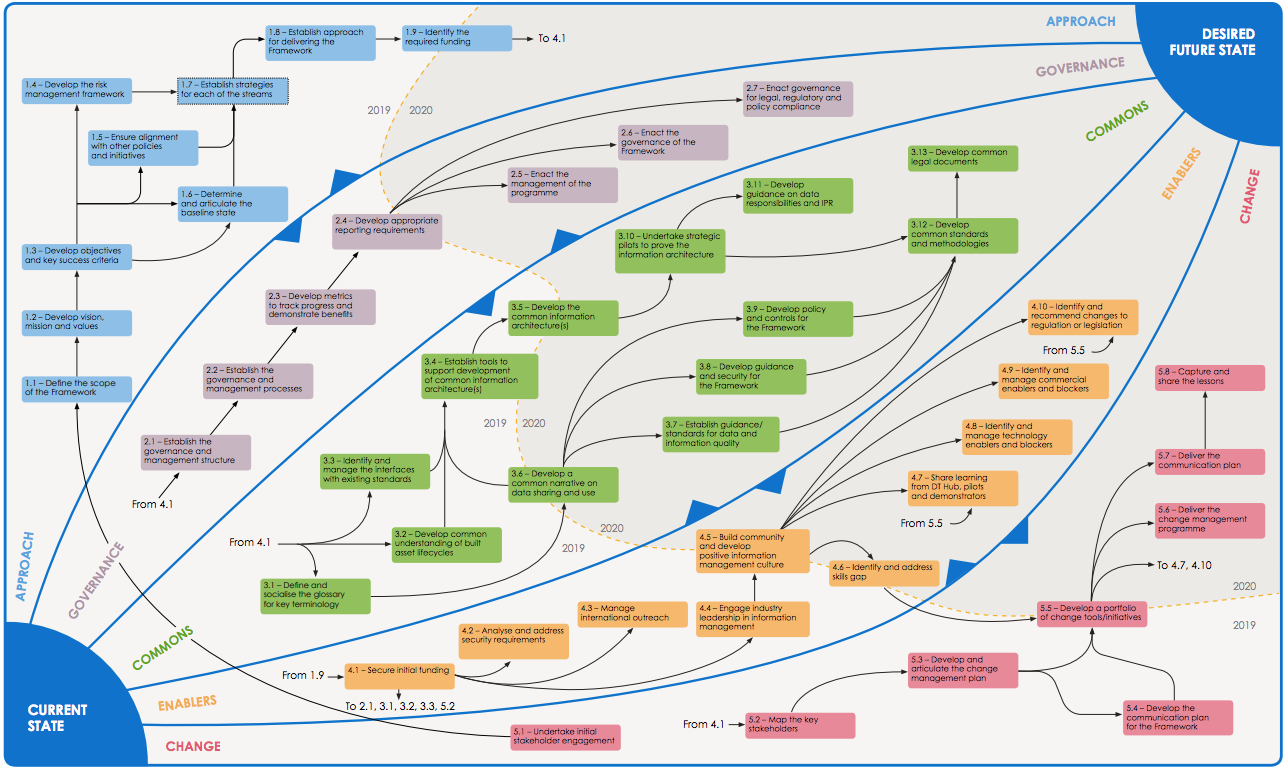

The Digital Framework Task Group (DFTG), launched in July 2018, is developing a digital framework that will help to unlock the value of infrastructure data and support the creation of a national digital twin (NDT): a federation of connected digital twins across all sectors and at a national scale. The ODI – along with other key stakeholders – is part of the DFTG and we plan to contribute to the ‘Commons’ track of the DFTG roadmap.

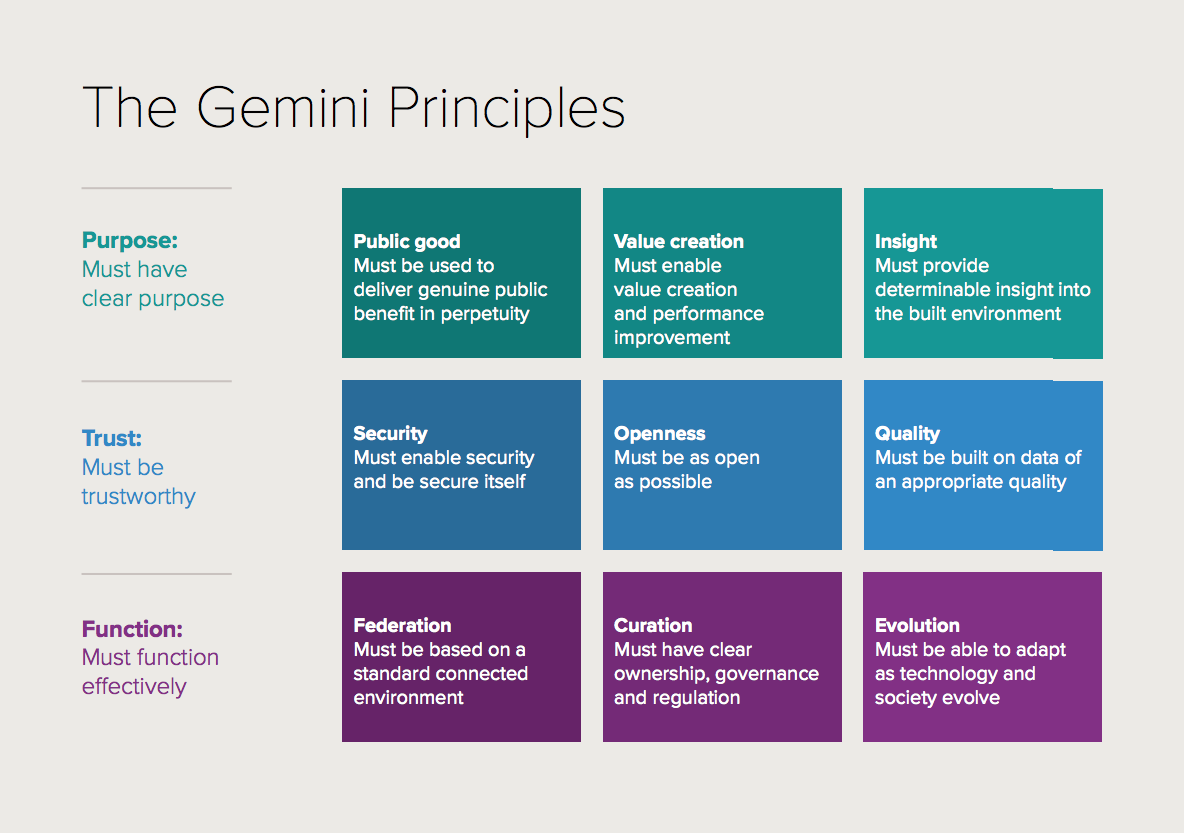

This track aims to support effective information management via guidance, specifications and standards. The first output of the group is a proposed set of principles – known as ‘The Gemini Principles’ – that set the direction for building stronger data infrastructure for the built environment. The ODI helped to develop these principles.

We have just started our new research and development project on digital twins and the first step has been to get a team together to explore the Gemini Principles from different perspectives.

We wanted to approach the principles from the perspective of someone being introduced to them for the first time. We formed a new team and asked questions around how a user might go about complying with the principles, to help us work out where guidance is needed.

What we found

- The Gemini Principles are ambitious – they aim to guide the development of the information management framework that will enable the development of the NDT over the course of decades.

- The principles have a broad scope – which means they can be interpreted in different ways, for example the principles are written to apply to both the Information Management Framework and the NDT, and it is also possible to read them in a way that applies to individual digital twins.

- There are tensions between some of the principles – some of the principles could be interpreted as conflicting with each other, eg open and secure, or public good and (commercial) value. This isn't surprising: the design of any system involves trade-offs and competing optimisations. Balancing the approach to implementation will help to manage these tensions.

- Distribution of value - Gemini Principle 2 states ‘value must be shared fairly within the NDT system’. Value may mean different things to different actors within the ecosystem and further clarity may be needed before implementation of this principle can be consistent. The ODI believes that everyone must benefit fairly from data. Access to data and information promotes fair competition, cooperation, informed markets, and empowers people as consumers, creators and citizens.

- Strong data infrastructure – embedding the need for digital twins to evolve by focusing on establishing strong data infrastructure rather than be driven by the latest shiny technology, will ensure resilience in the long term, and it is good to see this embedded in Gemini Principle 5 - Openness: that data infrastructure should be as open as possible.

- Openness can be applied to all elements – this principle could be about openness of process or openness of result, or it could be both. Looking at all the components of a digital twin (sensor data, modelling, software code, visualisation, insights, etc), it is interesting to think that some or all of those could be open while other components are only accessible on a shared basis, or closed.

- Openness while protecting privacy – the 'secure by design' point in Gemini Principle 4: Security could conflict with ‘as open as possible’ in the Openness principle. These two principles could be interlinked to foster the desired behaviours - we must make data as open as possible while protecting people’s privacy, commercial confidentiality and national security.

Questions we asked ourselves

Reading the principles generated some interesting questions that we will consider as we continue with our R&D projects. These are just a few of our burning questions:

- Will insights be gained at a national level? Is there ambition for how the NDT will be used in practice eg for strategic planning? How would you ask questions of the NDT?

- There will be a role for the private sector in availability of data for a NDT? -What will this look like? How will this be encouraged or enforced? This is something we highlighted in our paper ‘The UK’s geospatial data infrastructure: challenges and opportunities’.

- How will we manage tensions where public good and openness meet commercial interests, value creation and security concerns?

- Should the principles be stronger on the use of data while avoiding harmful impacts to individuals and groups? Some data assets accessed, used and shared in digital twins may need consideration from an ethical and legal perspective – eg where data is collected on car movements via tools like Automatic Number-Plate Recognition and CCTV. Increasingly, those collecting, sharing and working with data are exploring the ethics of their practices and, in some cases, being forced to confront their practices in the face of public criticism.

- How will the open processes and community in creating the NDT be supported?

- How do we recognise that different parts of a federated NDT will evolve at different rates, and ensure this doesn’t impact on connectedness, openness and quality of the data and insights?

- Could collaborative data maintenance play a role? Some nationally important geospatial data assets like OpenStreetMap or research projects like Colouring London are maintained through collaboration.

- Beyond the distributed nature of the NDT, what mechanisms do we envision supporting its evolution? The more you connect things, the harder, typically, it is to change them – and that is especially true for systems with hardware components.

We’re looking forward to continuing to work as part of the DFTG and help build a world where people, communities, organisations and governments use data to make decisions that improve people’s lives.

Get involved

Would you like to collaborate with us on this research and development project? Or do you have an idea for how we could work together to develop this or a similar new project? Get in touch here. We’d love to hear from you.