To realise the potential benefits of data for our societies and economies, we need trustworthy data stewardship. In this post, our Programme Lead for Data Institutions, Jack Hardinges, discusses the ODI’s ongoing work to test data trusts as an approach to stewarding data, and some of the recent developments in the field.

Definition

First, let’s talk about the definition. In October 2018 the ODI adopted a working definition of a data trust as ‘a legal structure that provides independent stewardship of data’. This followed our research earlier in the year that found multiple, sometimes conflicting uses of the term. The definition was intended to describe an approach to looking after and making decisions about data in a similar way that trusts have been used to look after and make decisions about other forms of asset in the past, such as land trusts that steward land on behalf of local communities. It was inspired by the work and thinking of others – particularly Lilian Edwards, Sean McDonald, Keith Porcaro and David and Richard Winickoff.

Over the past year or so, the definition has helped us to discuss, debate and design this type of approach to data stewardship, where one party authorises another to make decisions about data for the benefit of a wider group of stakeholders.

We’ve realised that, though implied, it misses what we consider an important (and perhaps differentiating) feature of a data trust: the fiduciary duty that the independent person, group or entity should take on in their stewardship of the data. In law, a fiduciary duty is considered the highest level of obligation that one party can owe to another. Sometimes they are established formally – for instance, a lawyer owes a fiduciary duty to their clients – and in other cases they are implicit, such as parents maintaining a fiduciary relationship with their children.

In the context of data trusts, a fiduciary duty involves stewarding data with this degree of impartiality, prudence, transparency and undivided loyalty. To reflect this, going forward we will adopt the definition of: ‘a data trust provides independent, fiduciary stewardship of data’.

As I will discuss, there is debate in progress related to how this relationship should be constructed, and where it’s necessary. Our work on the wider concepts of data stewardship and data institutions reflects our view that data trusts represent one approach to stewarding data. Acknowledging that there is both value to exploring data trusts as a particular approach and that there will be many scenarios where they will be unnecessary or unsuitable is okay.

Acknowledging that there is both value to exploring data trusts as a particular approach and that there will be many scenarios where they will be unnecessary or unsuitable is okay.

Different purposes

At the ODI, we’re interested in ways of increasing access to data to maximise its societal and economic value, while limiting and mitigating potential harms. We advocate for and support practices that demonstrate trustworthiness by: factoring ethical considerations into how data is collected, managed and used; ensuring equity around who accesses, uses and benefits from data; and engaging widely with affected stakeholders. Data trusts represent an approach to stewarding data that can conform to this.

We tend to focus our efforts on helping companies and governments to build an open and trustworthy data ecosystem. This means that we’re interested in working with organisations that hold data to build data trusts. Our first work to apply data trusts in practice with the UK Government Office for AI in April 2019 involved three separate groups of organisations looking to design and establish a data trust to steward data they had collected. Much as Keith Porcaro has written, this follows the idea of companies ‘[putting] their user-data in some form of irrevocable, spendthrift-esque ‘data trust’, which would then be managed by a third-party trustee (a nonprofit, for instance)’.

This does not mean that the data trusts we’re seeking to bring about will simply facilitate data sharing between organisations, or be more permissive than alternative forms of data stewardship. On the contrary, they will often apply a fairly significant degree of friction to data sharing – establishing where that friction is warranted is a big part of the challenge to be addressed.

They will often apply a fairly significant degree of friction to data sharing –- establishing where that friction is warranted is a big part of the challenge to be addressed.

We understand, however, that others may be seeking to advance the use of data trusts for different purposes. Sylvie Delacroix’s and Neil Lawrence’s proposal for ‘bottom up data trusts’, for example, describes a scenario where ’data subjects choose to pool the rights they have over their personal data within the legal framework of the Trust’. They seek to rebalance the respective control that corporations and individuals have over personal data, and provide a legal mechanism to empower data subjects to choose between different approaches to data stewardship that reflect their preferences and needs. Where data portability and other rights - and services like personal data stores - give people the ability to themselves decide who can access and use data about them, this use of data trusts seeks to enable people to appoint others to make those decisions, based on the argument that individualistic approaches to data stewardship are flawed.

As a Mozilla Fellow, Anouk Ruhaak is also working on scenarios where multiple people ‘hand over their data assets or data rights to a trustee’, such as data donation platforms that allow users of web browsers to donate data on their usage of different services. The work of artificial intelligence company Element AI similarly seeks to ‘understand whether data trusts could be a way to enhance protection for individual privacy and autonomy, [and] address existing power asymmetries between technology companies, government and the public.’ A write up of the 2019 workshop run by the Alan Turing Institute and Jesus College Intellectual Forum suggests that a data trust can only meaningfully be considered as such if it sets out to ‘support the collective assertion of data rights’ in this way. This description seems to tie together the attributes of trusts (the fiduciary duties they impart on trustees) with just one purpose, or scenario, where they might be usefully employed (the power asymmetry between organisations that hold data and data subjects). As others have also acknowledged, we think there are scenarios where organisations that hold data may usefully seek to establish and defer control to a data trust.

Data trusts also represent a way of stewarding data by and for the benefit of defined communities. In this context, data trusts are being discussed as a means to limit or prohibit access to data, and protect and maintain it as a community asset. Aimee Whitcroft has suggested they could be used in this vein to promote Māori data sovereignty. Jasmine McNealy, of the Digital Civil Society Lab at Stanford PACS, has already set out to question who benefits from the use of trusts to steward data, particularly when related to marginalised communities and established by civil society organisations.

Although respective actors and purposes may differ, the definition we are working to and our interests may be compatible with others’. Elsewhere, the use of data trusts will be entirely incompatible with what we as an organisation advocate for and support – such as using data trusts to ‘offshore’ data to avoid legal or financial responsibilities, or weaken existing democratic institutions and processes. The community-of-practice growing around the topic should remember that trust structures have been used by companies to obscure assets within secrecy jurisdictions as well as to steward land.

Different opinions

As well as different purposes for data trusts, there are emerging differences regarding the practicalities of creating them.

The legal form that data trusts should take has been a topic of significant discussion. The legal partners we worked with on our initial pilots found that ‘the mechanism of trust law is an inappropriate way of attempting to impose [the fiduciary duties typical of legal trusts]’, largely on the basis of their advice that data cannot be made the property of a trust under existing law. In October 2019, Professor Ben McFarlane questioned this finding, suggesting that people’s rights over data, such as those conferred by the General Data Protection Regulation, rather than data itself, could be made the property of a legal trust and asserted collectively by its trustees. A similar argument has been made by Sylvie Delacroix and Neil Lawrence, who have suggested that while there are challenges, they ‘do not constitute reasons to doubt that data rights can be held under a legal Trust’, and a paper published in the National University of Singapore Faculty of Law’s journal found that ‘the traditional trust, the historical creation of English Equity jurisprudence and now found around the world, is a perfectly sensible vehicle for the management of data’.

Others have gone further by arguing that, not only can trusts in the legal sense be used to steward data, they must be used to construct data trusts due to trust law’s unique properties and value. While we remain interested in this debate, our interpretation of the advice we’ve received – in short, that independence and fiduciary duties can be effectively imposed to the stewardship of data using trusts as well as other legal forms – means our ongoing work to apply and test data trusts is not reliant on it being resolved. We want to help bring about the trustworthy, sustainable stewardship of data that is comparable to institutions like the National Trust’s stewardship of parks and other land (which was first incorporated as a not-for-profit company in 1894 and is now a registered charity). Focusing only on the question of whether data can be held in legal trusts will not get us there.

In our initial work to pilot data trusts, we suggested various ways they might be funded. In some conversations we’ve had, people have assumed that every data trust will need to generate revenue by charging for access to the data it stewards or for related services, but we do not think this will always be the case. Providing access to data might align well enough with the objectives of existing organisations – such as those contributing data to it – that they will be willing to provide the resources required to set up and maintain a data trust.

Where a data trust does need to generate revenue to sustain itself, those involved should be conscious of not spanning too much of the data value chain. For example, if stewarding data from multiple organisations across a sector, it might usefully link or combine that data, but providing further services and analyses on top may preclude others from undertaking their own uses that would advance its purpose.

We also differ with others at a more definitional level. For example, we describe stewardship of data as collecting, maintaining, and sharing it, and in particular, deciding who has access to it, under what conditions and to whose benefit. Therefore, the use of data trusts by organisations involves them deferring some control, in the same way that legal trusts involve authorising trustees to control an asset. Some working on data trusts instead propose shared technical and legal environments for organisations where, as with BrightHive data trusts, ‘each data trust member’s data stays in their control and private’. This Humanities Commons proposal for ‘a data trust for industry data sharing’ would also seem to be missing this element of authorisation. Also, while our interpretation is not attached to a particular technology architecture, framework or vendor, others may use the term to promote services that are. For example, the Sightline Innovation Data Trust is a ‘smart-contract platform to secure and monetize your data’ and the Canadian companies Bitnobi and Tehama have launched ‘the only proprietary data trust solution in the market that manages the data tracking, auditing, and sharing activities when working in an enterprise organization’.

Something like TRUSTS (Trusted Secure Data Sharing Space), a recently launched EU-funded programme, is relevant to the topic of data trusts but dissimilar enough to represent a different approach to the one we describe. A search for data trusts, or a scan of the term on Twitter, will reveal many such projects and initiatives. This can sometimes make this a difficult field to navigate.

We’re a way off it always being clear where there is useful differentiation between different types, uses or applications of data trusts, and between data trusts and other forms of data stewardship.

Some have suggested that the term ‘data trust’ is being used as a ‘marketing tool’ and others have been accused of ‘trusts-washing’. While sometimes it is evident that the term is being abused, I think that we’re a way off it always being clear where there is useful differentiation between different types, uses or applications of data trusts, and between data trusts and other forms of data stewardship.

‘Show me the data trusts’

Over the past couple years we have often been asked to point to existing data trusts or attempts to create them. There have been many statements of intent, thoughts and papers published regarding the topic, but people are rightly interested in examples they can unpick. Our answer is often the following, long one.

Firstly, there are many existing examples of one party authorising another to make decisions about data on their behalf, for the benefit of a wider group of stakeholders. Organisations like HiLo, which takes data contributed by around 3,500 ships to generate risk and safety analyses, insights and recommendations that benefit the maritime sector, and Creative Diversity Network, an independent non-profit that stewards and publishes data about diversity efforts collected by UK broadcasters, are examples of this.

There are also examples of data-holding organisations going out of their way to become beholden to the advice or decision-making authority of independent interests. Groups like the Environment Agency’s Data Advisory Group have long provided advice to public sector bodies on their sharing of data, and from a more operational point of view, the myriad data review boards and independent ethics groups in the UK research space – such as Administrative Data UK and NHS Digital’s Independent Group Advising on the Release of Data – deliberate over prospective uses of data on behalf of the organisations that hold it. Despite its troubles, Facebook’s relationship with the Social Science Research Council is an example of a private sector organisation choosing to put in place a similar arrangement.

For ‘bottom up’ data trusts, there are analogous attempts to support groups of individuals to contribute data to an entity that stewards it on their collective behalf. Datacoup and LunaDNA are examples of these. As I’ve written about elsewhere, some personal data stores and personal information management systems also already operate under this kind of delegated authority, where they enable people to contribute data about them and defer some rights to decide who can access and use the data. It happens for non-personal data too. For example, in contributing data to a project like OpenBenches, people are authorising it to make decisions about the collective asset that the dataset represents.

Although operationally similar, the lack of fiduciary duties that the entities involved have in stewarding data would seem to be the difference between some of these existing examples and proposals for data trusts. As Mad Price Ball and Bastian Greshake Tzovaras’ work helps to point out, even where a legal form exists that might impose this type of duty, the way that data stewardship decisions are made on the ground might in fact be very different. As partnerships between data-holding organisations and foundations, academic institutions and other organisations are typically heavily influenced by the former group, we may also question the independence of some of these existing data stewardship arrangements.

I suggest that with data trusts, we are talking about the imposition of more explicit, contextual fiduciary duties, and independence, where the stewardship of data is the primary activity in question. To give an example, there is a difference between a charity that already, in theory, has trustees with a fiduciary duty to steward the data it collects and holds, and incorporating a charitable trust to steward data as its raison d'être.

There are, though, existing efforts to do this too. UK Biobank – set up in 2006 to steward genetic data and samples from around 0.5m people – takes the form of a charitable company with a board of directors that ‘act as charity trustees under UK charity law and company directors under UK company law’. It would seem to put into practice much of David and Richard Winickoff’s earlier proposal of ‘The Charitable Trust as a Model for Genomic Biobanks’. The UK company OpenCorporates’ work over the past couple of years to establish a separate entity with independent trustees to safeguard the organisation’s mission, and Truata, which provides privacy-enhanced data analytics solutions underpinned by a ‘unique trust structure [that] separates governance from assets and profit... governed by a trust deed’, may also meet such a description. In just the past couple of months, Facebook has created an independent oversight board to decide on content removal using a non-charitable purpose trust under Delaware trust law.

As Sean McDonald pointed out to me, Microsoft also appears to have experimented with a data trust to oversee access to customer data in Germany and John Hopkins Medicine describes itself as operating a data trust for the benefit of its patients. Sidewalks Labs’ proposal for an independent data trust to be used for data collected from the Quayside development in Toronto rumbles on.

I suggest that with data trusts, we are talking about the imposition of more explicit, contextual fiduciary duties, and independence, where the stewardship of data is the primary activity in question.

Our publications in April 2019 describe our own first attempts to experiment with data trusts. We intend to do more practical application, as well as conduct research and publish articles like this that address the theory. There may be other organisations who have put their own data trusts in place or are working to do so, but with no information about them – or the definition they are working to –in the public domain, they leave nothing for others to learn from and do little to push things forward.

This is an emerging field and it will take time for us all to identify existing data trusts and attempts to create them. Working in the open will help.

Where’s the demand?

We continue to come across a significant amount of demand for translating data trusts from theory to practice.

At a policy level, our work with the Office for AI reflects interest among governments in supporting the adoption of data trusts to enable data to be shared and used in ways that support new technologies dependent on data access, such as AI. Outside of the UK, data trusts have been included in the Canadian Government’s Digital Charter as a mechanism to support particular sectors, activities and technologies. The European Commission also named-checked ‘trusts’ as a personal data intermediary with significant potential in their European strategy for data published in February 2020.

Data trusts are also a popular topic at a city level. This is perhaps, in part, due to the growth of cities’ use of sensors and other equipment to capture data in public spaces. Here, data trusts may represent a way for citizens of a particular space to exert ‘community consent’, where individual consent (in a broad, rather than purely legal, sense) may not be feasible but citizens’ should still be involved in decisions about how data about them and their community is used.

Of course, organisations that see potential in the adoption of data trusts to further their mission and values – like the ODI and German think-tank Stiftung Neue Verantwortung – have fuelled interest in the topic. Academics and others interested conceptually do likewise; as do organisations that see a business opportunity in offering services related to them. In particular, the growing number of articles published by law firms on data trusts over the past year suggests more will become active in this space, and the major professional services firms are surely not far away.

I would like to see more robust testing of the idea in different, specific contexts.

Although our work to pilot data trusts has suggested that organisations that hold data might have their own reasons to permit a data trust to steward it, much of the demand for data trusts to date has been ‘top down’. It has largely taken the form of high-level proposals designed to tackle big challenges (such as power imbalances between organisations and individuals, or a structural lack of access to data across sectors). I would like to see more robust testing of the idea in different, specific contexts. This could include: deliberative engagement to understand the demand among citizens for a data trust to be used in a particular city or urban space; analysis of whether people or organisations who already contribute data to organisations to steward, such as in the examples above, feel that fiduciary duties and independence are missing (or not!); and research to assess whether people are willing and able to become trustees of data. This would help to better flesh out the demand for data trusts, and the characteristics of scenarios where they are required.

An interesting development in the past year or so has been the proposal for data trusts to be mandated where there aren’t incentives or demand among organisations that hold data to adopt them. For example, Evan Malmgren has suggested that ‘the state delegates eminent domain to a newly established independent trust that seizes control of all data generated by [a platform’s] users’ if that platform has been deemed anticompetitive. On a panel at the ‘Competition Matters’ conference run by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung in November 2019, I was asked to propose data trusts as a mechanism to increase competition in the same way that data portability has emerged as a tool among competition authorities and other regulators to do so. More notably, the Head of Competition Law Policy of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy, Thorsten Kaeseberg, observed that an expert German panel has recommended a study into ‘the feasibility of the establishment of […] data trustees and introducing instruments at the European level to promote the emergence of trusted data intermediaries’ to the European Commission.

Away from competition, there is also interest in the mandated use of data trusts to unpick control from large technology platforms over what researchers are allowed to access data they hold, and thus to tackle their significant influence on research and policymaking. This discussion has parallels with the way that trusts have been established by law in the past to correct perceived market failures, as well as the way that independent groups have been implanted by law to help steward data held by the public sector (such as the Health Research Authority’s Confidentiality Advisory Group in the UK).

Also relevant in thinking about demand is the importance of being clear where you or someone else is advocating to create something new or to change something existing. For example, when I hear someone describe ‘a data trust for Uber data’, I question whether they’re proposing a new entity to steward data contributed by Uber drivers about their activity (that they may have gained control of by using their rights to data access or portability), or the reconfiguring of Uber itself to become, or become beholden to, a data trust.

The difference is a significant one, and as Peter Wells has recently pointed out, the sometimes instinctive reaction to create something new rather than improve the existing might be misplaced, especially in the context of government and its existing responsibilities to steward data. I think this is also particularly true of organisations originally established to practice a particular form of governance. At a recent University of California, Irvine workshop I attended, I got the impression that the assembled collection of credit unions left thinking more about how they could manage data about their customers in ways that better align with their principled, cooperative management of funds, rather than creating a new data trust to house the data they’d collected.

Throughout our work on data trusts we have been keen to stress that they do not ‘solve’ data stewardship, nor represent a silver bullet. They exist on a wide map of approaches, some less explored than others.

It’s for this reason I enjoyed Dr Ingrid Schneider’s presentation at MyData 2019, which scrutinised the fiduciary trust alongside other possible answers to the question ‘Who Governs the Data Economy?’. The Ada Lovelace Institute’s Rethinking Data programme, designed to change the data governance ecosystem through research and public engagement, looks like it will assess the challenge of data stewardship through a similarly wide lens.

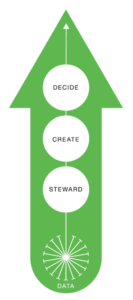

At the ODI, we consider data trusts as an emerging form of data institution. As an institution is an organisation devoted to a particular cause, especially of a public, educational or charitable character, then a data institution is one whose cause is primarily the stewardship of data in this vein.

At the ODI, we consider data trusts as an emerging form of data institution. As an institution is an organisation devoted to a particular cause, especially of a public, educational or charitable character, then a data institution is one whose cause is primarily the stewardship of data in this vein. We hope that the concept of data institutions will support our efforts to bring about the stewardship of data that maximises its value and protects people from potential harms.

We’ll continue to publish on our attempts to apply data trusts, specifically, and research on the topic of data institutions, more widely, as we go.