With the support of the Patrick J. McGovern Foundation, in 2023 the ODI began investigating how the development and maintenance of global data infrastructure can enable access to data and facilitate collaboration to support research and innovation aimed at addressing pressing global challenges. After an in-depth mapping of challenges in this space, we have focused on enabling access to social media data to support public-interest research. We are continuing this research through research collaborations including the CoCoDa project, working together with the University of St. Gallen, the University of Lausanne and Maastricht University over the next 4 years to integrate technical and legal expertise to identify key solutions to this challenge.

This page presents some of the findings and resources produced by the programme and serves as a call to action for people, communities and organisations interested in collaborating on this research with us.

What is global data infrastructure and why is it important?

Data such as statistics, maps, real-time sensor readings, and experiment results help us to make decisions, build services, gain insight, and develop new scientific theories and innovations. As our economies and societies become ever more reliant on generating value from data, it is becoming increasingly important to build and maintain the vital data infrastructure that makes it possible to effectively collect, manage, use and share this valuable data, and to do so in responsible ways. In this interconnected world, our data infrastructure will need to become increasingly global as well.

One area where the development of global data infrastructure could have a major impact on people, communities and societies, is in the area of research and innovation. As was made clear by the impact of sharing health data during the Covid-19 pandemic, there is enormous potential value to increasing access to data and insights for research and innovation – not just in areas like health where data helped to track the spread of Covid, but in taking action to address the impacts of climate change, supporting evidence-based policy-making, combating exploitation and the spread of disinformation or harmful content online and confronting democratic and societal polarisation and fragmentation.

However, as the recent pandemic also made clear, building and maintaining global data infrastructure to increase access to data for research and innovation is complex and challenging. Doing so requires working across geopolitical boundaries, sectors, industries, disciplines, technical standards, and legal regimes. Bringing together these different contexts requires coordinating across a large number of stakeholders, each with their own requirements, goals, and legacy systems. It sometimes involves breaking down silos and often exposes contradictions and competing interests that complicate the development and maintenance of global data infrastructure.

To address the pressing challenges of our time, it is imperative that we understand the best ways to build and maintain global data infrastructure.

What we focused on

In order to drive progress in this area, we are investigating how the development and maintenance of global data infrastructure can enable access to data and facilitate collaboration across boundaries to support research aimed at addressing pressing global challenges.

This is obviously a very large topic, so we began by conducting desk research and expert interviews to identify and prioritise challenges and research questions worthy of investigation. See below for some of the topics we have identified. Ultimately, we have been focusing on the question of how to enable public-interest researchers to access data currently siloed within private entities. There are many different approaches to enabling access to privately-held data, such as through supporting private-public partnerships, mandating access through legislation, paying for access, building data institutions to facilitate safe access, and/or through utilising privacy-enhancing technologies to enable access while protecting sensitive information. We want to understand the benefits and limitations of those approaches and identify ways of increasing access where possible.

Specifically, we are keen to identify ways of enabling public-interest researchers to access data held by social media companies. The importance of social media companies is demonstrated not just by their reach (Meta had 2.9 billion monthly active users and over half of the global population use some form of social media), but by their impact on everything from political movements and elections to social interactions and the physical and mental health of users. As a result, it is imperative that researchers are able to access data held by social media companies in order to investigate these impacts. This is true not just for academic research, but for journalism, open-source investigations, advocacy, policymaking and regulatory oversight. In past years, the value of accessing this data is demonstrated by the range of important research and findings that are enabled by it, such as the causes and impacts of teacher resignations during Covid-19, electoral disinformation and the prosecution of potential war criminals in international tribunals.

Unfortunately, many social media platforms have recently rolled back access to data that was previously made available for researchers. This includes X, Meta and Reddit. As a result, collecting and using this data is increasingly challenging for researchers worldwide. Many are forced to rely on data that is self-reported by platforms such as transparency reports, or risk being pursued for breach of contract by collecting data through means that may violate platform terms and conditions (eg web scraping).

This programme aims to identify ways for different types of researchers from different countries and regions to access important data held by social media companies to support public-interest research.

What we investigated

Within the programme, we are investigating different aspects of this challenge. First, we are seeking to understand how different countries across the globe are attempting to enable access to social media data. Recently, governments in the United States, United Kingdom, and Brazil (to name but a few) have introduced legislative proposals to enable researcher access to social media data, but to date, the only policy that actually mandates researcher access to platform data to come into effect is the Digital Services Act (DSA) in the EU. Article 40 of the DSA mandates that providers of prominent social media platforms grant European researchers access to data for research aiming to detect, identify, and understand systemic risks within the EU. But even the DSA has some gaps and uncertainties; there is a lack of clarity regarding the application process that researchers must navigate, what constitutes ‘commercial ties’, what research questions are in/ out of scope, what the vetting process should look like and how access will be enforced. We are continuing to compare and contrast these efforts in different countries in order to understand which emerging approaches can/ cannot be transposed to countries with different social contexts, regulatory bodies, and sociotechnical infrastructure.

You can read more about our research on this topic in our short exploratory report, based on interviews with experts worldwide about the challenges of accessing platform data in their respective regions. We believe this will help researchers and policymakers working in different regions identify shared challenges and potentially identify areas for future collaboration.

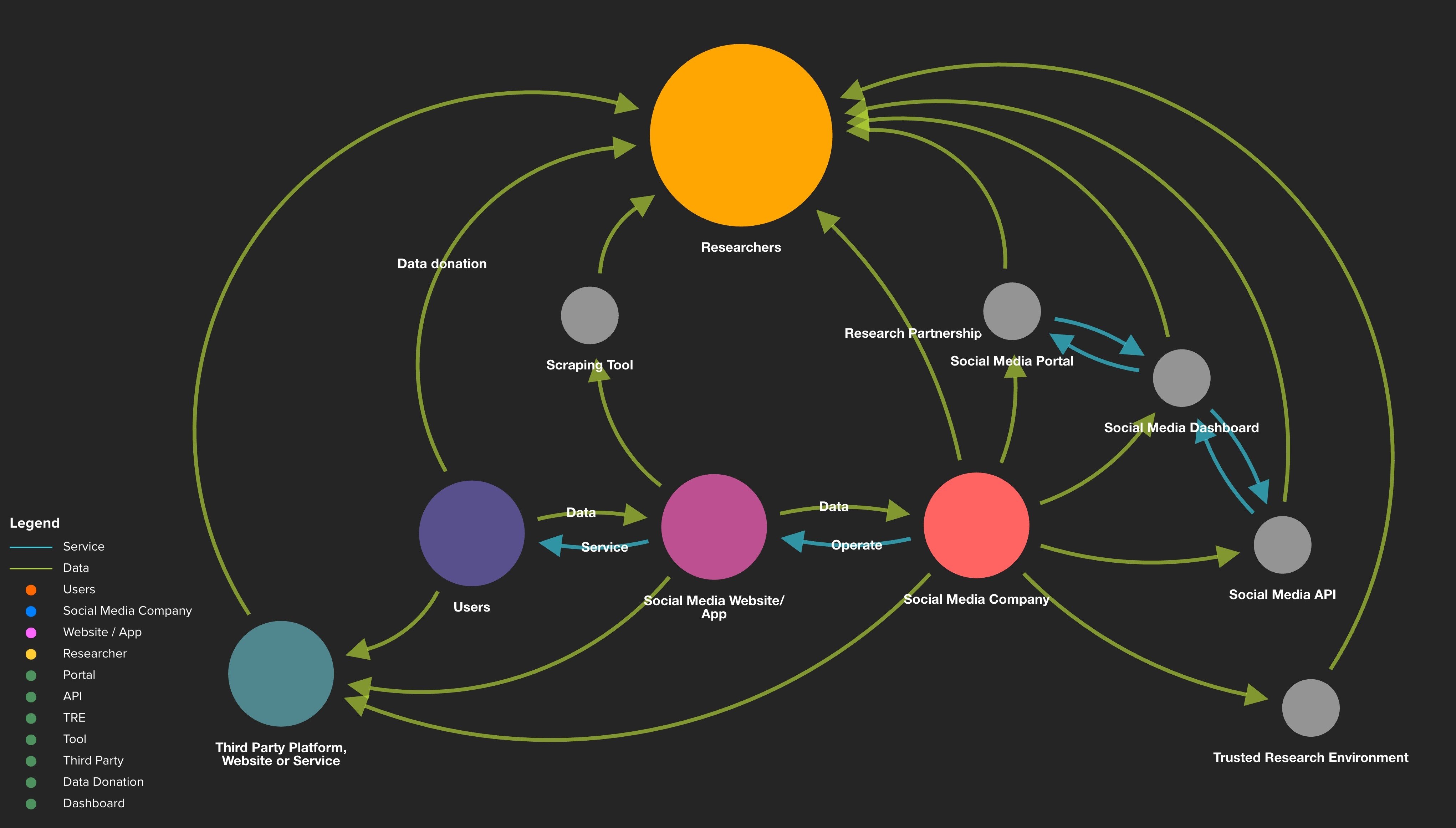

Second, we have sought to understand how public-interest researchers are seeking to access social media data outside of systems mandated by regulations. Not only are any new regulations mandating access to social media data likely to take years to be drafted, debated, ratified and enacted, even those mandates are likely to leave out many people conducting research in the public interest - eg journalists and open-source investigators that exist outside academia and more formal research organisations. To aid our understanding, we have mapped the different approaches available to researchers that are attempting to gain access to social media data. Our research identifies four main ways that researchers can access data about social media platforms: directly from the social media companies; directly from the platform/ app; from users of those platforms/ apps; and from third parties, which may have originally collected the data via any of the previous three routes.

You can find out more about our efforts to map these approaches in our annotated slide deck which introduces a work-in-progress typology of different access models. This work builds on the ODI Data Access Map. Feedback from presenting this typology at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media suggests that this type of guidance is needed within research circles. The typology can help public-interest researchers understand the range of different ways they can already gain access to certain types of social media data as well as explore approaches that might serve as inspiration for future access initiatives.

Third, our work on the typology of access models has helped us identify one major approach to accessing social media data that researchers seem to be increasingly gravitating toward: scraping or crawling ‘public data’ - eg data that is published on news websites and social media platforms. A challenge frequently raised in our initial discussions with researchers and stakeholders is the lack of clarity around what constitutes ‘public data’, and therefore a lack of clarity around what constitutes fair collection and use of that data. They feel that in some ways this lack of clarity is limiting – or intentionally being used to limit – access to important data. The lack of clarity around what researchers are allowed to scrape also potentially leaves them in a legal and ethical grey area when collecting or accessing this type of data. This can lead to a chilling effect, deterring important public-interest research due to fears of costly litigation. To help address some of these challenges, we are working to develop a proof-of-concept Delphi survey that can serve as the foundation for future consensus-generation exercises. In order to continue gathering viewpoints and evidence, the survey will remain open for the time being. Please feel free to submit a response and share it with your communities if interested.

You can learn more about our development of the Delphi survey in our short project write-up. We aim to conduct further consensus-generation exercises with partners across the globe, with the long-term goal of helping different stakeholders (eg different types of researchers, regulators, policymakers, digital platforms/ publishers, industry bodies and customers/ users) begin to agree on what should and shouldn't be considered 'public data' and establish early-stage guidelines for ethical use.

What we produced

Written outputs

- Exploratory report: Exploring global challenges of regulating researcher access to platform data

- Annotated slide deck: ‘Accessing data about social media platforms for public-interest research’

- Public data pilot study writeup

- We must fix researcher access to data held by social media platforms, Sasha Moriniere in the ODI’s Medium publication Canvas

- Locked doors: researcher access to social media data — a reading list, Sasha Moriniere in the ODI’s Medium publication Canvas

- CoCoDa project launch blog - our 4 year research collaboration

Shared resources

Resources airtable: ‘ODI register of initiatives that enable access to social media data’

Conference sessions and presentations

- Co-delivered a tutorial at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media

- Tutorial web page: ‘Scraping Reddit the Right Way: A Guide to Legal and Ethical Data Collection with RedditHarbor’

- Tutorial slide deck: ‘Tutorial at the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media’

- Participated in the ‘Right To Research’ panel at the Computers, Privacy and Data Protection conference

- Presented an examination of global data sharing trends in health at the AI Executive Program: Digital Healthcare conference

- Contributed to the co-design of global data sharing systems at ‘Leveraging EUDR as an opportunity to build more inclusive and sustainable supply chains’