When building new institutions, like data trusts, we need to understand the risks and harms that they could cause. We used Pokemon Go to to do just that.

We have been looking at a range of approaches for data access recently with a particular focus on institutional approaches to data governance – things like data trusts, clubs and cooperatives. In these approaches people and organisations permit the institution to make decisions about how data is used and shared. Different models have different mechanisms for making decisions, for example through independent trustees or democratic decision-making by members.

One of the areas we will be doing more work on is how to understand and mitigate the risks that these new institutions can pose. This will help people building them, people scrutinising them, and people who need to build regulatory environments around them.

Understanding the risks of a potential data trust

After our first wave of data trust pilots we published various reports and recommendations, including a prototype data trust lifecycle to help people building a particular data trust. One of the activities in that lifecycle was to understand risks.

When the team got back together it was one of the things we wanted to work on. Doing it ourselves will help us produce guides that make it easier for other people to do it. And by doing it on enough examples it might help us zoom out to the more systemic challenges that new institutions can pose.

We knew that trying to understand the risks of a completely conceptual data trust would be hard so we had to pick a particular example to explore. After some debate we decided to pick an old favourite, Pokemon Go.

'A Pokemon Go data trust is not the best idea, but it is useful to play with'

Pokemon Go is an augmented reality game that encourages people to walk around the towns and cities where they live while hunting fictional creatures. The game already features in our introduction to data ethics course, where attendees debate the ethics of how data is used in the game, and has also been used in our data ecosystem mapping work.

We wondered if the data captured by the game could be used to improve the cities where Pokemon Go is played – for example, data about the flow of people around the city, about new streets, or about places of interest might all be useful for city policy makers, businesses and community groups.

A Pokemon Go data trust could help balance the differing interests of the business that makes Pokemon Go (Niantic); the people who play the game; the people who might use the data; and the people who might be impacted by it. Balancing conflicting interests is one of the potential benefits of a data trust.

To be clear. We do not think a Pokemon Go is the best idea for data to help cities. The data is unlikely to be particularly helpful on its own because it is not complete enough. We came up with the idea because it was ‘real enough’ to help us explore the risks. And because it was fun.

We combined Doteveryone's consequence scanning tool with our ecosystem mapping guide

There are various techniques for identifying risks. We use specific techniques for particular risks (for example how to manage the risk of reidentification of individuals) and sometimes use our Data Ethics Canvas to help us understand potential questions to explore, but as we have already explored Pokemon Go's data ethics we wanted to use another approach.

Doteveryone has recently published its Consequence Scanning tool. It is designed to help organisations consider the potential consequences of their product or service on people and society and provides an opportunity to mitigate or address potential harms or disasters before they happen. We thought the prompts from the tool were particularly useful so combined them with our ecosystem mapping tool into an exercise.

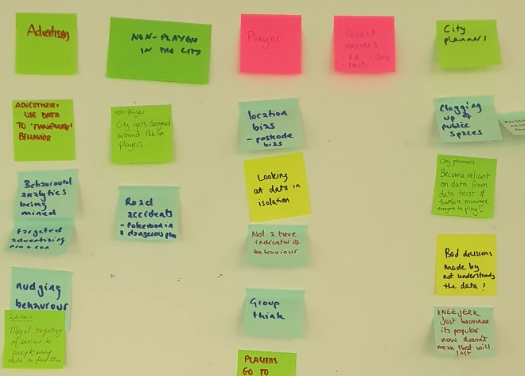

The team started by exploring what the purpose of a Pokemon Go data trust would be and what it intended to achieve. This helped us understand the basics. We then listed the range of actors in the ecosystem surrounding the data trust, for example game players and game non-players, city planners, the business that built Pokemon Go, other businesses, criminals, and central government organisations that might seek access to the data - for example for investigating crimes such as fraud or terrorism.

We then used the prompts in Doteveryone's consequence scanning tool to start thinking about what could go wrong and how these might actors might cause harm to each other.

Finally we used dot voting to select some risks to investigate in more detail. In each case we considered whether it was a significant risk, how we could reduce the chance of it occurring, and how we could reduce the impact if it did. The risks we explored were:

- City planners becoming reliant on making decisions that use data from the data trust, and therefore encouraging people to play Pokemon Go so that they get representative datasets.

- Data that could be opened is restricted in data trusts.

- The data trust starts to monetise data in a bid for sustainability.

- The data trust becomes a target for malicious actors, either through technical hacking or through attempts to capture the trust's decision making processes through the trustees

We learnt a few things from the workshop

We learnt that we could use tools like our Data Ethics Canvas and Data Ecosystem Mapping tools, and Doteveryone's Consequence Scanning guide to produce a long list of risks. We could see that we then needed to use more traditional risk management approaches to prioritise and manage those risks.

Second, we saw that several of our risks could be mitigated by a good definition of the purpose of a data trust. This purpose would be built into the legal structure of the trust. It will affect the behaviour of the trustees and hence the trust as a whole. Developing good guidance for purposes might head off many risks.

Third, we know that institutional approaches have different types of risks but this initial work helped us start to think about categories. A future guide to determining risks might get people to think about different stakeholders or different categories of risk. That can help to ensure that there is adequate coverage. Four potential categories are:

- delivery risks: that impact the build and operation of a particular data institution. These can break down into sub-categories like strategic, operational, financial, people, regulatory and governance

- purpose risks: that the creation of a new institution, or change to an existing one, might create new dependencies or dynamics that could affect the reason for creating it or hinder you from achieving it.

- systemic risks: that a particular institution poses in the broader data ecosystem – whether it be to data holders, data users, other intermediaries, beneficiaries or broader society.

- systematic risks: that the whole concept poses to the broader data ecosystem.

Each category may need to be tackled by different actors. For example delivery risks, such as the failure to secure sustainable funding, are likely to be mitigated by organisations building data trusts while some systematic risks, for example that unclear legislation leads to gaps in responsibilities and harm to people, are the responsibility of governments.

Understanding the risks of new institutions, and how to tackle them, will be one of the things that inform our work exploring how institutional approaches to data access and governance could help build an open and trustworthy data ecosystem. New and unexpected risks exist with new institutions. That is why we have recommended that people experiment with them carefully.

As with our previous work the next phase will include a mixture of practical pilots and cross-cutting basic research.

If you have thoughts on this blogpost or would like to work with us then get in touch at [email protected].