Author: Jack Hardinges

As part of its innovation programme, the Open Data Institute (ODI) is connecting data innovators across the UK and France through a combination of events, bilateral projects and research. In this blog post, we compare the approaches to open banking in France and the UK, and the role of the respective governments in supporting data portability.

This is a timely topic: today, the ODI and PWC have published a report, The future of banking is open: how to seize the Open Banking opportunity which examines how the financial services ecosystem and technology firms are responding to open banking. It also describes the significant market opportunity created by open banking, as well as its potential to disrupt the financial services landscape.

The term ‘open banking’ is used to describe the evolution taking place in retail and consumer banking. It involves the process of banks and other financial institutions opening up data for anyone to access, use and share – such as product descriptions and branch locations – as well as the sharing of transaction and account data by bank customers to trusted third party organisations. Open banking is expected to increase competition between banks and to fuel innovative new products and services for consumers.

Open banking is part of a growing trend towards people gaining more control over the way that data is collected, used and shared. The mechanism which allows people to share data about themselves – held by organisations, in this case banks – with other products and services is often referred to as ‘data portability’.

Some organisations enable users of their services to do this already, such as when we give a smartphone app permission to access photos. In some cases, regulators have intervened in an attempt to make data portability happen. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), for example, equips people with the right to data portability.

PSD2 as the driving force behind open banking in Europe

There is a driving force behind open banking in Europe: the revised Payment Services Directive (PSD2). The directive was designed to make it easier, faster and less expensive for consumers to pay for goods and services, in part by requiring payment account providers to allow third-party access to data they hold. It applies to all EU member states (since its introduction in January 2018) although some parts of the directive will not be finalised until September 2019.

Each EU member state is expected to adopt PSD2 by transposing the content of the directive into their own national legislation. Therefore, in Europe, there is a combination of factors shaping open banking including: the regional directive; national regulation; the decisions and actions of banks, financial institutions and other organisations; and the expectations and needs of customers themselves.

Beyond aligning their national regulations with the directive, however, there are differences in the ways that the UK and France have responded to PSD2 and in the ways they have supported open banking more broadly.

UK from the Open Banking Standard to Open Banking Implementation Entity

In the UK, banks were given an open banking head start. The UK government-commissioned Data sharing and open data for banks report – produced by the ODI and Fingleton Associates – was released in late 2014. Following its publication, the UK Treasury announced a call for evidence to examine how an open application programming interface (API) standard (infrastructure to support the sharing of data) could be delivered. It then worked with the ODI to convene the Open Banking Working Group (OBWG), which collaboratively produced a detailed framework for the development of an open API standard.

In 2016, the OBWG, under the joint leadership of the ODI and Barclays, published the Open Banking Standard (OBS) framework as a guide to how banking data should be created and shared. The initial scope was limited to: shared data from individual and business current accounts, savings and credit cards; and open data about product offerings and the locations of branches and ATMs.

Following the publication of the OBS report, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) ordered the establishment of an organisation to oversee the implementation of the OBS with a requirement that the nine largest retails banks and building societies must implement the standard within a particular timeline. The Open Banking Implementation Entity (OBIE, also known as Open Banking Limited) was funded by these banks and buildings societies. The CMA also mandated a competition to encourage innovation around the emerging APIs – the £5m Open Up Challenge was established to support and reward teams developing next-generation services, apps and tools for UK small businesses.

The work of the OBIE and the groups that preceded it has laid the groundwork for UK banks to adapt to PSD2. The initial limitation of scope and focus of the CMA’s intervention seems to have encouraged action and reduced the initial implementation burden, despite that fact that not all the nine banks met the initial CMA deadline this year (2018). The OBIE has also addressed issues of trust and liability by developing systems and processes for enabling access to data held by the banks, limiting access to third parties who have been approved by the Financial Conduct Authority.

In November 2017 the OBIE announced that it will expand its focus to the other payment account types set out in PSD2, which includes credit cards, e-wallets and prepaid cards, as well as further enhancements mandated by the CMA. This will extend the work of the OBIE into 2018 and 2019, and demonstrates the continued role of a number of organisations in supporting UK banks and other organisations to adapt to open banking.

France – an open banking charge led by Stet

The French open banking landscape looks quite different to the UK’s. Whilst an ordinance putting PSD2 into national legislation – amending France’s Monetary and Financial Code (MFC) – was published in August 2017, there has not been significant government involvement in open banking. The Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution (an independent administrative authority which monitors the activities of banks and insurance companies in France), for example, did not issue guidance in response to previous EU payment directives and is not expected to do so for PSD2.

Without the intervention of an organisation such as the UK Treasury or the CMA, France’s open banking charge has been led by Stet, a payment processor owned by France’s six major banks. In 2016 Stet begun development of an API standard to support the sharing of customer account data and the initiation of payments by third parties, working with the Fédération Bancaire Française, as well as other European and international organisations. It published the first version of this standard in 2018.

Stet is also part of the Berlin Group, a consortium of almost 40 banks and other organisations from across the EU attempting to build a pan-European standard in response to PSD2. The group has developed a standards framework, NextGenPSD2, and has put it out for public consultation. The group’s work demonstrates an attempt to develop standards and approaches that span Europe.

UK and France as an illustration of different international approaches to open banking

So far, open banking in the UK and France has taken rather different forms. The UK government has intervened in an attempt to push the retail banking market to develop and implement a common standard, while the French government appears to have taken a more laissez-faire approach.

The differences in the ways that the UK and France have supported open banking is indicative of differing international approaches. Mexico has recently passed a FinTech law that includes open banking provisions. Japan’s Financial Services Agency expects its banks to have open APIs in place to make data available to third parties by 2020. Conversely, the Monetary Authority of Singapore has recently announced that the nation’s “transition towards ‘open banking’ can be more successful if it takes place without the regulator mandating action” and is advocating for an ‘organic’ process. In the US, API standards were published in 2018 that are similar to the requirements of PSD2; many banks are expected to adopt them despite them not being obligated to do so.

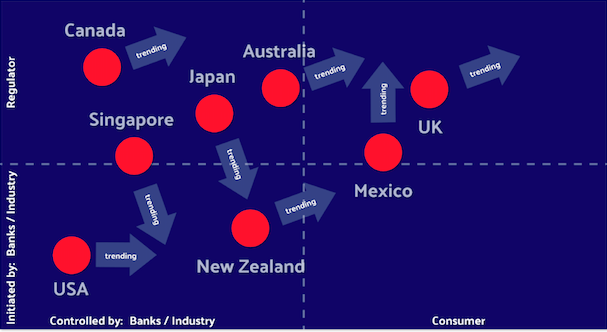

Bud, a UK-based platform that links together different financial services, recently published its Open Banking Global Snapshot, covering developments in Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore and the USA. The report includes a matrix that describes the origins and direction of travel for these nations’ open banking initiatives:

Going forward it will be interesting to see how the open banking efforts in France and the UK converge. The European Commission has stated that banks and other organisations have until September 2019 to implement final technical specifications related to PSD2, but it’s unclear exactly how developments made by the OBIE, Stet and the Berlin Group will comply or need to be adapted. For organisations working across the EU harmonising national standards may also prove difficult.

In both countries groundwork has been laid for open banking, if yet not the explosion of new products and services for consumers it promises.

The ODI helped develop a community to collaborate on developing the UK Open Banking Standard and is working with other sectors and countries to develop similar things. We also recently published an open standards guidebook to help organisations find, adopt and create open standards for data. Get in touch if you would like to know more.