For data holders thinking about increasing access to the data they hold, the ‘data access models’ available to them are many and varied. These ‘models’ are basically the collection of procedures, mechanisms, agreements and structures that organisations can put in place to fashion a data access arrangement that suits their needs

But before we, as data holders, users, researchers, regulators and policymakers, can engage in informed discussions about the various models, we must understand what they are, how they are different and what the pros and cons are of each.

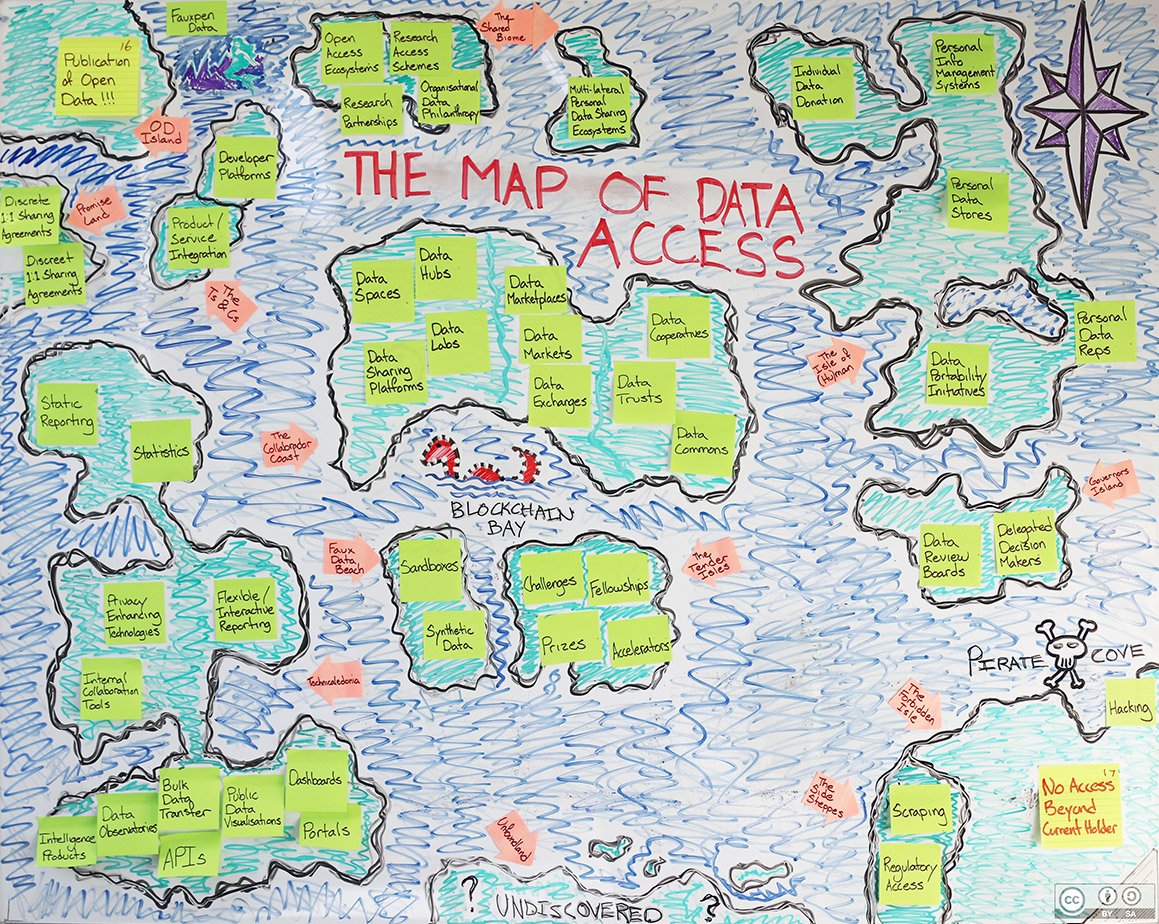

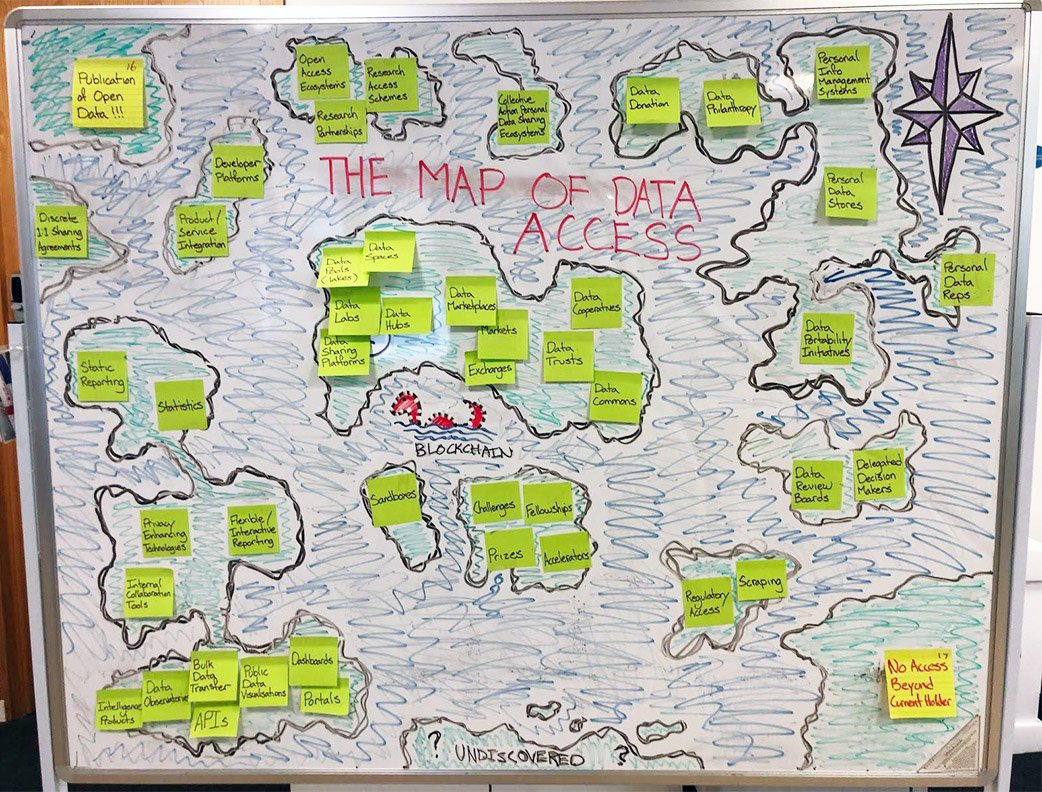

An ‘Archipelago’ is a word to describe a chain, or cluster, or collection of islands, or sometimes a sea containing a small number of scattered islands, and we’ve created what we call ‘The Data Access Archipelago’ as part of our efforts to help people navigate these complexities. It is a difficult challenge, but one we think is important and, much like the high seas in the sixteenth century, worthy of exploration.

Anchors aweigh: our exploration of the world of data access

We began our research with a simple, two-part question: “Can we construct a taxonomy of data access models, and would such a thing be useful to data holders thinking about increasing access to data?” There is a range of different models out there for increasing access to data – some established, some less than established – so we set out to break those models down into their constituent parts and build them back up into groups based on shared attributes.

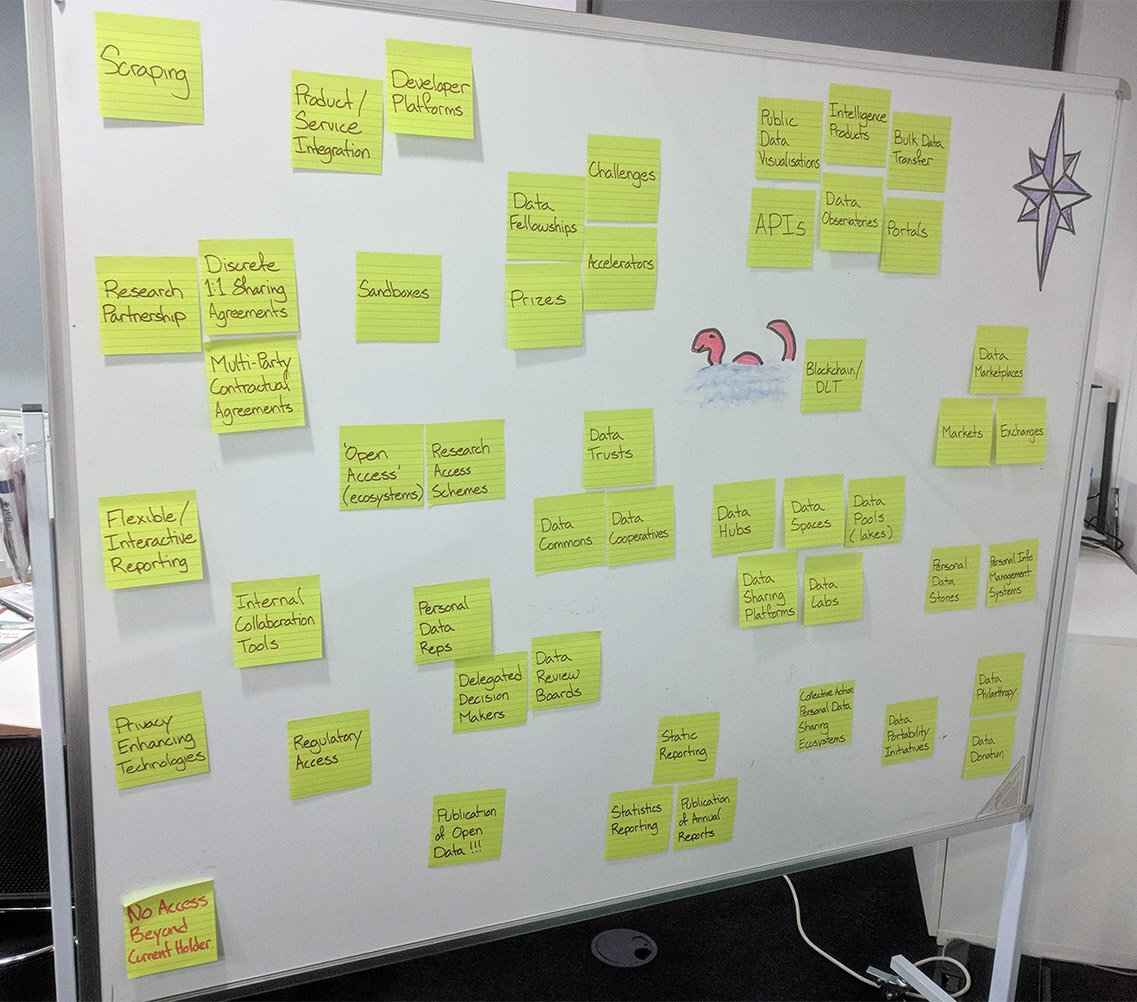

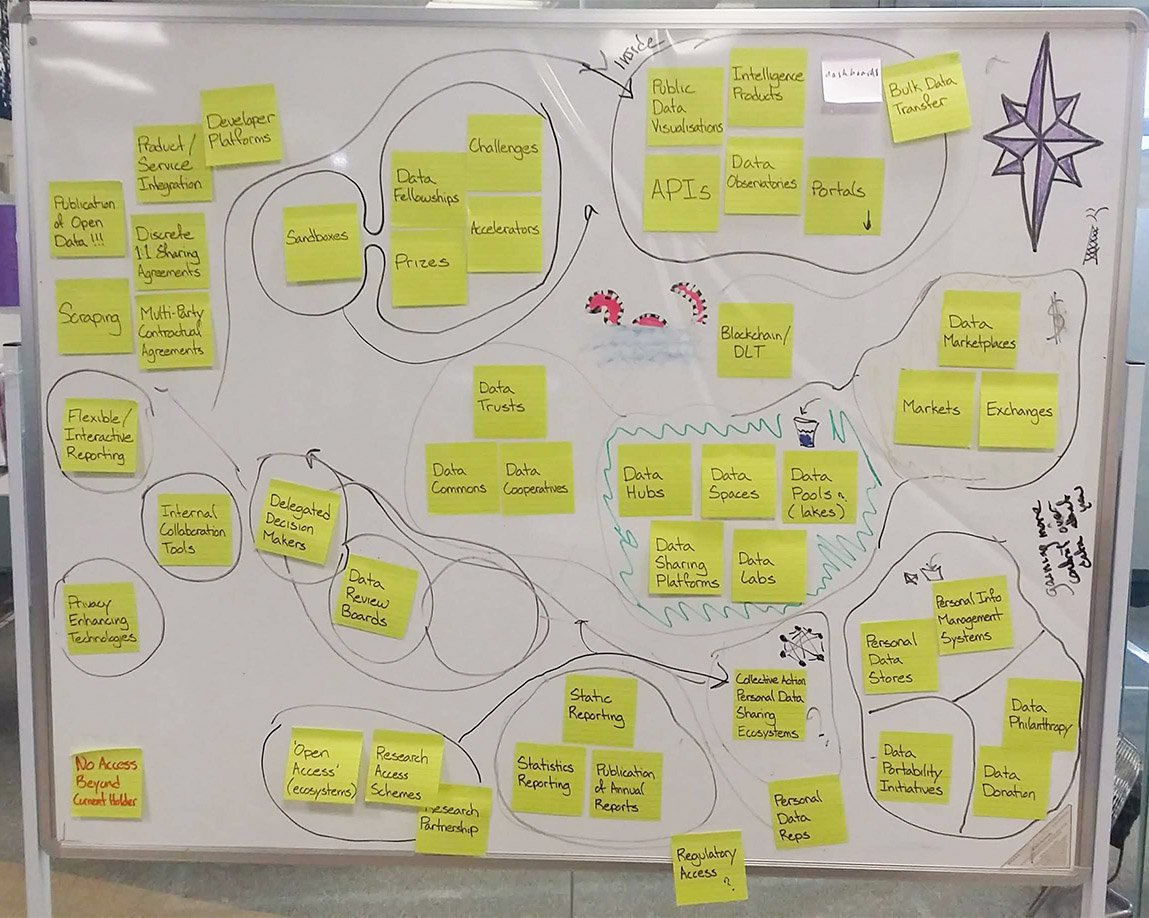

Our first step was to identify the dozens of different data access models currently in use or being discussed. We then spoke to other organisations working in this area in order to see how other people have approached this challenge. Much of the work involved deconstructing a variety of data access models ‘in the wild’ in order to identify the structures, processes, mechanisms and relationships upon which they were built.

We found that while it’s possible to group data access models based on shared characteristics, there’s a good deal of overlap between models and attempting to compare some models is like comparing apples and some fruit nobody’s ever heard of.

Taking a different tack: clustering models by shared characteristics

Our research showed us that a taxonomy may yet prove practicable and valuable, but we decided the best course forward – for the time being – would be to cluster the models based on a few shared characteristics and to then place those clusters on a map as the various continents, islands and isthmuses. For instance, our map contains a cluster of models aimed at facilitating collaboration (The Collabrador Coast); a cluster of technical mechanisms for increasing access to data (Technicaledonia); and a cluster of models concerned with advertising for and attracting skilled partners (The Tender Isles). For certain clusters it was sometimes possible to differentiate the models further – thus the isthmuses connecting the landmasses that make up the Isle of (Hu)Man.

In the end we tried to place each cluster near related clusters. The Side Steppes, for instance, contain a cluster of models aimed at gaining access to data that another organisation has chosen to (or attempted to) keep closed – they therefore lie on the western edge of the Forbidden Isle.

Like many maps from the age of exploration, our map is imprecise and unfinished, with large landmasses yet to be discovered. And, like many of the maps carried by latter-day sailors, our map may include fibs or inaccuracies, and possibly even areas of (real or perceived) danger.

We think that in addition to helping us demonstrate the range of data access models that exist, this map of the Data Access Archipelago will help us show that we are all still discovering new approaches and developing a common language. We also believe it will help us highlight the variety of ways that people are working to make better use of existing models and exploring new territory.

Learning the ropes: disentangling imprecise and often ambiguous terms

During our research we found that while there are many data access models currently in use, the models that people often talk about are neither discrete nor mutually exclusive. The terms used to describe the various models are indistinct and often overlap with terms used for other models.

We can expect a bit of overlap given the complexity of the real world, but it can also contribute to a lack of clarity and precision within discussions about increasing access to data. This can be seen not only in the confusion surrounding the term ‘data trusts’, but in the ambiguity surrounding things like data collaboratives, data cooperatives and data commons. People find themselves unwittingly talking about different concepts, different challenges and different solutions.

Meanwhile, what people refer to as data access ‘models’ are often only one aspect of a much larger and more complex access arrangement: prizes, challenges and fellowships are methods of attracting capable partners and collaborators; data review boards and personal data representatives are governance and decision-making processes; APIs, portals and public data visualisations are technical mechanisms for increasing access; and data hubs and data sharing platforms are primarily ways of pooling data in order to facilitate collaboration within a shared (yet controlled) environment.

Also, since many of these models deal with disparate aspects of data access arrangements, they can be, and often are, combined. Take a hypothetical example: a corporation and a university might pool their data in a data cooperative in order to put on a data challenge. Initial access to sample data could be provided through an API, after which applications would be assessed by a data review board which would then allocate access to the full dataset via a data hub.

Complex combinations of models such as this might take form over years or even decades, with different pieces being added at different times to address different concerns or opportunities. If we look at our map, this hypothetical data access arrangement would take us on a voyage from the eastern shores of the Collabrador Coast to the Tender Isles, down to Technicaledonia and over to Governors Island before dropping anchor on the western side of the Collabrador Coast – a long, complex journey indeed.

Crucially, data access ‘models’ are not self-contained, end-to-end solutions to increasing access to data. They are not silver bullets. Organisations looking to implement a data access model will need to make decisions related to governance, oversight, enforcement, ethical review processes, technical mechanisms, legal structures and stakeholder engagement.

These decisions will be heavily influenced by a complex set of factors, including: the sector (eg medical versus environmental research); the context (eg cultural approaches to data, privacy, authority, trust); the type of data (eg an individual’s internet browsing history versus a listing of public toilets in Newcastle); the scope (eg national versus international scale); the granularity of analysis desired (eg access to high-level trends versus item-line detail); the purpose (eg revenue generation versus regulatory compliance); and the number and background of the parties involved.

A data access arrangement that worked in one instance in a particular context with a particular set of legal, technical, governance and decision-making structures might not work in another without significant changes or additional structures.

Close quarters: the increasing presence and prominence of third parties

Organisations are increasingly installing third parties and intermediaries to play a range of roles within data access arrangements: there are third parties that can provide arms-length governance, enforcement, ethical review, and legal and procedural oversight; parties that can act as aggregators, gatekeepers and matchmakers; even parties that can conduct initial research on soon-to-be-shared datasets on behalf of the parties involved. There are also third parties that can act as agents of trust through accreditation or certification procedures.

In many of these cases, the goal appears to be twofold: providing independent, third-party assurance and delegating risk. These third parties are playing a number of worthwhile roles, including controlling the number of people who can gain access to data and ensuring that those who are allowed access use it in an appropriate way. Third parties and intermediaries cannot solve every challenge, however, and it can be difficult to find the right balance between the benefits of providing access to data on the one hand and safeguarding privacy and protecting against harms on the other. Finding that balance often requires data holders/stewards to engage in conversations and debates with stakeholders about the potential benefits and harms.

In the wake of the Cambridge Analytica scandal, for instance, Facebook announced a new initiative to “help scholars assess social media’s impact on elections”. The initiative features independent, third-party oversight of the application and data access procedures and goes a way toward addressing some of the concerns and problems with Facebook’s previous data access procedures. However, as others have argued, in seeking to guard against potential harms, the new initiative may overly restrict access to this valuable data, ultimately limiting the potential benefits.

At the ODI we have written about the need to chart a course between a data ‘oil field’ future, where organisations hoard data, and a data ‘wasteland’ future, where unaddressed fears stemming from legitimate concerns (such as how data is used and by whom) cause people, governments and organisations to share data less frequently, thereby preventing society from realising the full benefits of data.

All hands on deck: the importance of collaboration and joint-ventures

The challenge for data holders when picking a suitable data access model, is to identify the right combination of governance, oversight and enforcement mechanisms, ethical review processes, technical mechanisms, legal structures and stakeholder engagement strategies so that everyone can benefit from data-informed decision making while being protected from any harmful impacts. Providing more comprehensive guidance for data holders to help them navigate the complex map of data access models is a difficult, but important, challenge that will take more time.

We will continue exploring this territory, and will keep you updated on other bits of our research and what we intend to do next.

If you are a data holder looking for guidance about the various options available to you, do get in touch. If you have thoughts about how to improve our map or would like to support our work, we would love to hear from you as well.