Collaborative data maintenance is when individuals, organisations and communities work together to collect and maintain shared data assets. The approach can help share the cost of data collection and management across different organisations and sectors, and can support the creation of a sustainable, trustworthy data infrastructure.

Well-known examples of collaboratively maintained open data sets include OpenStreetMap, Wikidata, Discogs and MusicBrainz.

We carried out a research and development project, Collaborative data maintenance, which aimed to explore how a collaborative data maintenance approach can and has been applied; and to inspire similar projects and institutions that share the goal of the curation of high-quality data. The work was part of a £8M, four-year innovation programme, running to March 2021, funded by Innovate UK, the UK’s innovation agency.

Through the project, we created a Collaborative Data Patterns Guidebook, to help people design and run projects that involve collaborative maintenance of data.

The project supports the Open Data Institute’s (ODI) mission to build an open, trustworthy data ecosystem, and help create a stronger data infrastructure that is supported by independent stewardship, is built on open standards and relies on common reference data.

Key facts and figures

- We directly participated in four open collaboration projects in early 2019 to learn more about the practice of collaborative maintenance.

- We ran five research interviews with people working on collaborative data projects, including Wikidata, OpenStreetMap, MusicBRAINZ, Wikipedia and dbpedia

- We developed 65 patterns developed, each of which describes a reusable, proven solution to a commonly occurring problem in collaborative data maintenance.

- Since publication of the Collaborative Data Patterns Guidebook, we have disseminated the work via social media to over 50,000 followers, with some enthusiastic responses as shown below.

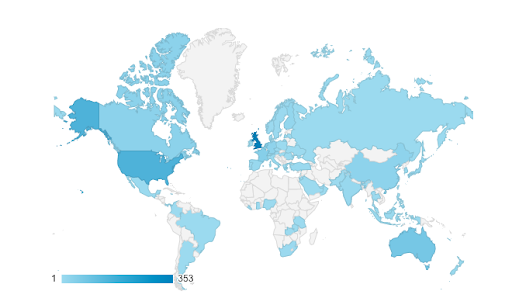

- The guidebook has attracted just under 1,000 users since launch in October 2019. Just over a third (37%) were from the UK; and just under two thirds (63%) from outside the UK, spanning 62 different countries, from Austria to Zambia.

- 946 users across 62 countries, from Austria to Zambia (Source: Google Analytics)

We had great feedback through social media, including:

Just finished reading @ODIHQ collaborative data guide and it's GREAT. Loads of great patterns in here, even for data projects with narrow participation. https://t.co/nPoe9lOwZT Already influenced my thinking and excited to make these patterns work in https://t.co/j1CrsYOBZt! — Simon Worthington (@51M0NW) November 19, 2019

and

Haven’t read this properly yet but at a skim it looks great. Collaborative data patterns from @ODIHQ https://t.co/ci0JnJqq2m Perhaps now more people will understand why data and digital are a material for collaboration or coordination of activities. — Cassie Robinson 🏳️🌈 (@CassieRobinson) November 19, 2019

What was the ODI’s role?

We compiled a list of community data projects and carried out desk research on what makes projects successful. We looked at how the designers of these often very different projects manage the interests and experiences of individual contributors to create good quality data.

To really understand the approaches, we became contributors. We contributed to and learned about to projects including OpenStreetMap, Wikidata, Discogs, MusicBrainz, OpenCorporates, Zooniverse, Democracy Club, the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISDB), Mozilla Voice, Open Food Facts, Encyclopedia of Life, Open Plaques, eBird, and Open Library. We also observed the work of the Missing Maps who used the ODI office space for a short period, as a way to learn about the team’s approach, which helped inform the project.

In contributing to the projects we looked for common approaches (patterns) that result in good data maintenance. We observed the stakeholders’ interests, the scope of the project, what role the contributor has as a creator of data, common user experiences, and how it felt to be a new contributor.

In our analysis of the community data projects, we identified two axes for the openness of contributions: the range of contributors (some projects only allow specific people to contribute, whereas others allow contributions from any interested party); and the scope of the project (from very narrow to completely open-ended). Projects that are at different positions on either axis may require different approaches to support their contributors, and as such might contribute to the context in which a design pattern will be appropriate.

We identified the different roles that contributors play in the different projects, for example as holders of knowledge, as pattern recognisers or as witnesses in verifying data provided by others or providing observations.

The approaches for accepting contributions and managing interactions varied according to the role of the contributor in the project. Some projects enable direct user input, some have a moderation system, and some involve human-to-human interaction, for example via forums, ‘talk pages’ or web forms.

We held interviews with people working on collaborative digital projects to understand what they might need from a guidebook. Through these, we found out about the challenges faced and lessons learned through developing successful projects, and we gathered tips and recommendations for people designing similar projects.

The main output of this R&D project was the Collaborative Data Patterns Guidebook, an online resource that includes examples, practical solutions to problems and useful resources. Our hope is that the guidebook can help service and product designers across the public and private sector to create new applications that use collaborative approaches.

The guidebook is published under an open licence, for anyone to access, use and share. The full source code is available on GitHub. The guidebook has a ‘How to contribute’ page and people can contribute by: suggesting a new pattern; suggesting an alternative name for an existing pattern; submitting wording improvements; submitting new patterns; and discussing changes submitted by others in the GitHub project.

The guidebook includes a collection of design patterns that capture our learning from existing projects.

The patterns cover:

- suggestions for ways to design workflows

- how to encourage contributors to keep data up to date, fix errors and increase coverage

- how to manage a community of contributors

- what governance procedures to put in place

- and how to manage conflict.

The guidebook was featured in our newsletter, The Week in Data, on 11 October 2019, going to over 13,000 subscribers. In March 2020, we reshared the Collaborative Data Patterns guidebook as part of our response to the coronavirus pandemic, recognising the importance of community data projects during this time.

We also presented the Collaborative Data Patterns Guidebook at a variety of events including the Mozilla Festival 2019, a workshop at the Royal Society, a British Computer Society event, and Northernlands 2.

What was challenging?

It was more difficult than we envisioned to gain a real understanding of how existing collaborative data projects work. We started our research by spending time learning about how Wikidata and OpenStreetMap actually work and how to make expert contributions. We had a day’s training on the history, functionality and governance of these projects, which are two of the most complex community data projects. It took some time to understand the mechanics behind these projects, but it was time well spent as it helped us to really get to grips with how a successful collaborative data maintenance approach can be applied.

Managing all of the initially suggested patterns within the project timescale was a challenge. As we progressed, we realised we did not have time to refine and review some additional patterns, and instead we added them as issues to GitHeb to encourage further discussion.

We also found that it is difficult to allocate time to maintain the guidebook beyond the scope of the project. The funding and resources, for this and other similar projects, are often related to the specific project, and therefore there may not be further resources available to invest into maintenance, development and improvement.

What went well?

Trying collaboration projects for ourselves was rewarding and insightful. As well as observing the nature of the projects themselves, we also experienced what it felt like to participate in an unfamiliar domain of experts. Examples of contributions include classifying galaxies on Zooniverse, adding our vinyl to Discogs, donating our voice to Mozilla Voice, and downloading OpenFoodFacts on our phones and scanning our lunches. Although some projects were easier to pick up than others, the process was very rewarding and felt like we were taking part in something with a higher purpose, and it helped us to really understand how these projects work for new contributors.

Keeping focused on the primary objective helped move the project forward. This was quite a short project and a lot of research had already been done about the systems surrounding collaborative data. So we made sure we focused on figuring out the concrete, reusable tools and patterns that make a successful project, and developing the guidebook that would host this information.

The workshop and participation in projects as contributors motivated us to look in greater detail at various aspects of collaboration. The insight this work gave us led to a lot more questions than we had to begin with, which we then used desk research and interviews to answer. This gave us richer insight into the whole process of collaborative data maintenance.

What have we learned?

Hands-on research helps when developing best-practice guidance. We wouldn’t have been able to produce the Collaborative Data Patterns Guidebook unless we had first-hand experience of contributing to collaborative data projects. Spending time contributing to these projects enabled us to see what approaches helped and supported new contributors, and how they could be guided to make useful contributions. For example, for each project we asked a series of questions, such as ‘where do I start?’, ‘how do I know if my contribution is valuable?’, ‘what do I do if I’m uncertain or have a problem?’ and ‘how easy is it to make a contribution to an unfamiliar domain?’. Asking these questions helped us to develop the patterns within the guidebook.

Sustained promotion is needed to raise awareness and improve usage. The unique page views in the first quarter after the guidebook was published (October–December 2019) accounted for 1,497 unique page views, just under half of the overall unique page views since launch (3,067). This means the guidebook achieved around the same number of unique page views in its first quarter (1,497) as it achieved across the entire following year (1,570). This skew ties in with the initial promotion of the guidebook in October to December 2019, through the Week in Data, informal promotion with stakeholders and collaborators and social media. While we did present the guidebook at events throughout the year, a long-term marketing campaign around the guidebook may help to keep a raised level of awareness, and to promote the guidebook at key points throughout the year.

Long-term sustainability should be considered when developing microsites. Microsites can easily become forgotten with staff turnover and new organisational priorities. It is important to have a long-term plan for maintenance, promotion, technical support and content review and to build in these considerations at the start of the project, when considering its sustainability and viability for the future.