Data portability is often discussed as a way to increase innovation and competition in the economy, and here we compare our policy expectations in the real world to changes in the model

We built an agent-based model (ABM) of data sharing in a simple economy because we wanted to better understand how policy changes for greater data openness might affect innovation. Although the ABM is too simple to extrapolate from, we can still use it to think through policy issues and refine the questions we ask about interventions in the real world.

At the Open Data Institute (ODI), we have been debating the merits of greater data openness and whether these might motivate government intervention in support of data portability, which we described in a blog post in 2018 as:

In its broadest sense... the ability to share data between people, groups and organisations. A company, for example, might ‘port’ data – which could involve the transfer of data, or the provision of access to it – to a third party in order to deliver a particular service.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is an attempt to encourage data portability by giving consumers the right to obtain data held about them by organisations, not least ‘for reuse across other services’. Our model tries to capture the basic elements of data portability: in the model, companies can make requests to each other for data, with the likelihood of the request being granted dependent on the ‘policy environment’ – whether a company has low, medium or high levels of data openness.

The ODI has been describing some of the effects that we would expect to see after the implementation of the data portability elements of GDPR and similar schemes. These include that there might be greater competition, or that having access to data from more people might allow young firms with new ideas to create better products – and we have applied them in the model. Doing so tests our ideas against the economics that inform the model.

Data portability will induce more innovation

The ODI expects data portability interventions for data sharing to increase innovation by encouraging the development of similar products and services, and radically new products and services. It’s not just that companies’ increased access to data will allow them to better meet the needs of consumers, but it will also enable them to create products and services that they had not previously thought of – data versions of Henry Ford’s ‘faster horse’, if in fact he ever uttered the phrase.

To find out whether greater data sharing would lead to increased innovation – as we expected to see in the model – we gradually worked out a set of model options that maximise companies’ levels of innovation . This ‘high innovation’ scenario includes the following features and is compared below to the ‘base case’ scenario:

[table id=14 /]

We assumed that the ‘high-innovation scenario’ would show that data would easily flow between firms; consumers would be content to share personal data during consumption; and the development of new products would not be hindered by a privacy shock that made consumers recoil.

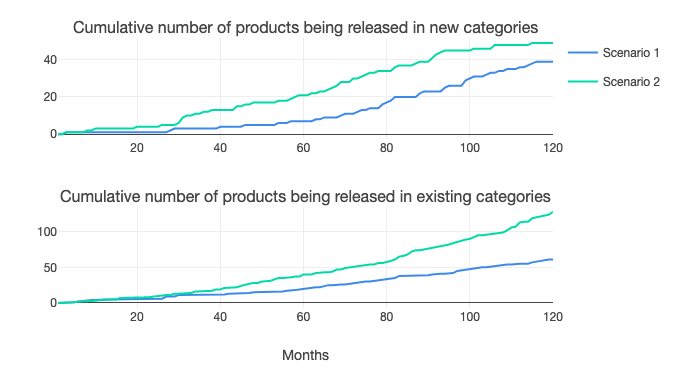

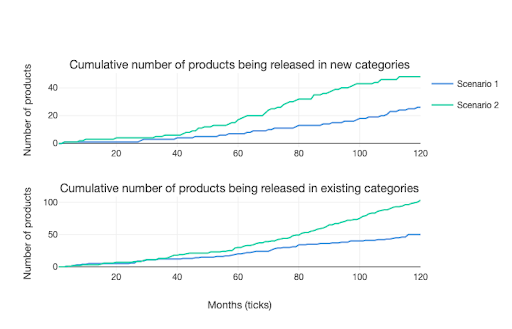

As you can see from the graphic below, the high-innovation case raises the development of products in existing and new categories to a much higher level than under the base case. The outputs from the model allow us to see that, while companies in scenario 2 – the high innovation case – have released many iterations of products in existing categories, they also push much further into exploiting the potential of new products.

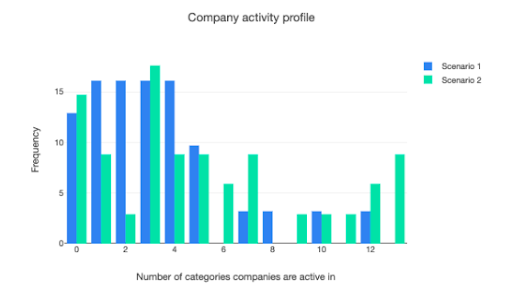

The innovation effects of data sharing are also shown in figure 2, which reflects figure 1, in that companies have made products in more categories in the high-innovation case than the base case. This also means that they are producing more complex products, as newer product categories combine more datasets than older ones – a feature built into the model design.

Data portability might increase competition but could also lead to greater dominance by large technology firms

The ODI has argued that data portability will lead to more competition in the provision of data-enabled goods and services. Companies know that their rivals might be able to attract data from consumers by providing more valued products and services and by being more trustworthy with personal data.

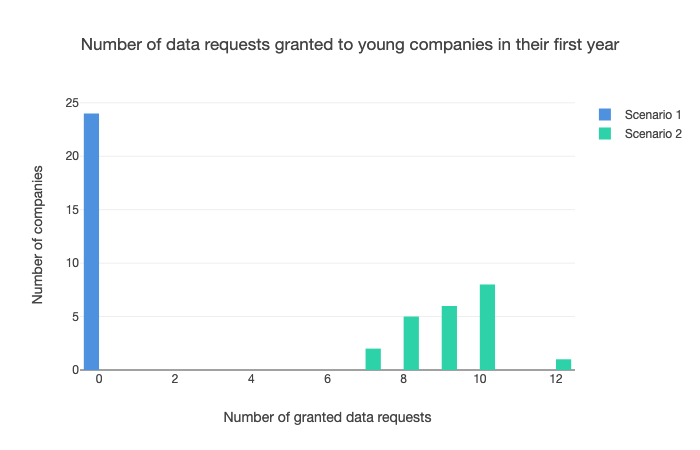

Our model proxies data portability in a simple way: companies make data requests to each other when they want to make a product that might meet a consumer need. This is a more realistic scenario than one in which consumers make the requests themselves, at least in the absence of data intermediaries who will manage the technological demands for them.

In the high-innovation case with large amounts of data porting – scenario 2 below – many more companies have their data requests granted than in the base case, which is shown by the high blue bar in figure 3. This is to be expected, but the greater data sharing also appears to encourage more dynamism across the model’s product categories.

You can see from figure 4 below that many more companies are entering categories to offer new products in scenario 2, while the rate of exit from categories is also somewhat higher – a sign that the product categories are a little more dynamic and hence more ‘competitive’ with more data sharing.

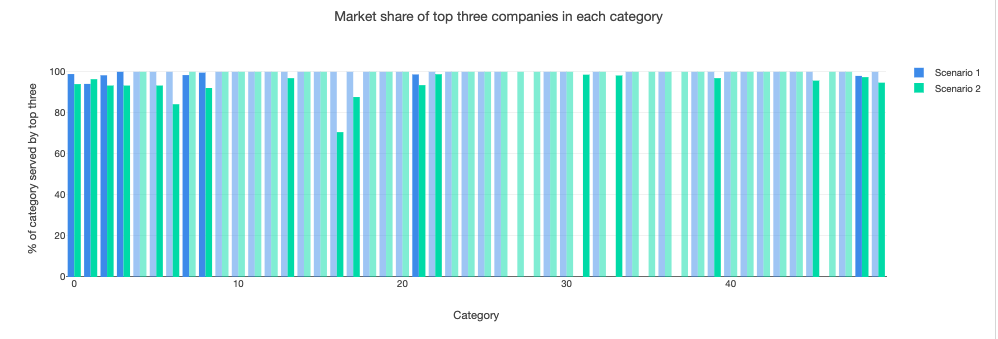

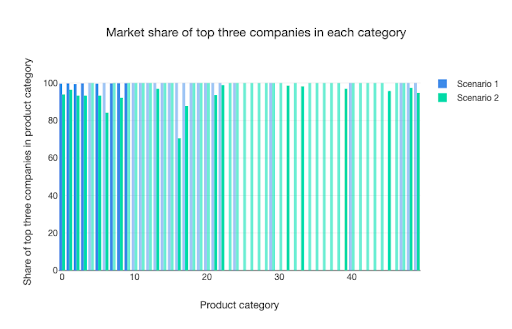

But the signs of greater dynamism don’t appear to lead to much diminution in market share held by the biggest companies. The graphic below shows that the base case in scenario 1 leads to some product categories not being dominated by large firms, but this could be because they are subject to a privacy shock and their peers in scenario 2 are not. This lack of significant reduction in market dominance – at least in the way that the concept is proxied in the model – could be because both scenarios start with some large companies which exploit their advantageous position as the model runs.

Data portability will mean the proliferation of personal data across multiple services

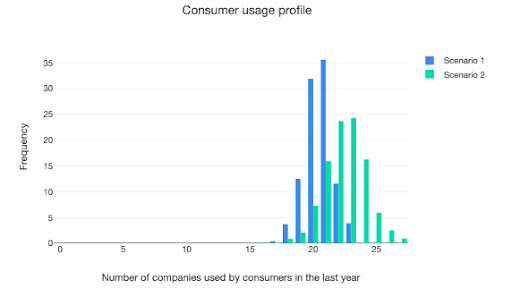

Greater data sharing allows companies to use more information about consumers but it could also lead to data about consumers being spread across more companies. The model allows this proposition to be tested in its thumbnail economy, as one of the outputs shows the number of companies that consumers are using in the last year of a model run. And as figure 6 shows, greater data portability encourages consumers in the high- innovation case to use more companies, and in doing so to provide personal data to more organisations than they do in the base case.

Data portability will not lead to much innovation if there are significant data leaks and consumer trust falls

There isn’t a direct measure of consumer trust in the model, but its effects on data sharing and innovation can be seen in the model through several of its outputs. The graphic below runs the base case in scenario 1 but with four big companies rather than two affected by a significant data breach, and compares it with the high-innovation case in scenario 2. And as you can see, this change reduces market dominance in a great many of the product categories, with almost no big companies establishing leading positions in the most complex ones.

This effect also means that there is little market entry in those complex categories, shown by figure 8, and much lower innovation as a result, which you can see in the second figure low.

The model shows how the ODI thinks the effects of increased data portability might play out, but only in the simple conditions offered by the model. To learn more about the many facets of policy in this area and how they might affect company behaviour and innovation in the real world, have a look at our work on the banking, retail, and peer-to-peer accommodation platform sectors.

Get in touch

We’d love to hear from you. To discuss this topic, or anything else around data policy, please get in touch.