A tweet from grime artist JME prompted Head of Content Anna Scott to consider how data can skew the presentation and interpretation of art, friendship and society

It’s a familiar scenario. I’m on a bus home to South London from a couple of post-work drinks with a friend, observing the people around me, listening to music, reading a little and, inevitably, scrolling through things on my phone with no particular intention.

Passively sated in this half-conscious, automatic act, it’s jarring when something pops up that points out its absurdity. Scrolling through Twitter, no doubt motivated – however consciously – by the prospect of a few new followers or a few more likes or retweets, a video pops up from the grime artist JME with a simple message: “Get rid of counters on social media please.”

Get rid of counters on social media please. pic.twitter.com/dj9o4750nt— Jme (@JmeBBK) August 9, 2018

It’s an interesting ask from someone with just shy of a million Twitter followers himself.

“We need to have a full year of no stats, no visible stats, no friend counter, no like counter, no view counter. No numbers. It’s social media – it’s social. We don’t socialise with numbers,” JME explains to camera.

“When I meet my friends to go and eat I don’t ring each group […] and go to the group with [the] most people there. I go to meet my friends that I like because I like them, not because they’ve got more friends with them […] We don’t have numbers when we’re being social in real life. Online we’re governed by numbers and it’s so hard to ignore them.”

Online we’re governed by numbers and it’s so hard to ignore them

JME goes onto admit that even he finds it hard to promote a song he loves on YouTube, if it has only 50 views. He adds that brands – who’ve become so accustomed to working without scrutiny with ‘influencers’ with the highest numbers of followers – should be digging deeper to find who they really want to work with and why that is.

It’s a refreshing angle, and strangely comforting to hear someone talk so honestly about the tension that comes with the opposing feelings of validation and comfort, and alienation and self-awareness that come with living our lives online.

It put me in mind of conversations we have a lot at the ODI about ‘data and the self’, both informally and through projects we work on, like our Data as Culture and Research and Development programmes.

One of the best parts of working in an open office with inquisitive people is that rich discussions happen all the time between us on the desk, in meetings and over our instant messaging platform, Slack. When I suggested writing a piece about this in a message on Slack to my editorial assistant (and friend) Steffica Warwick this morning, it struck a chord.

“I think there's also something in there about authenticity,” Steff said.

“We want more data, because we want an accurate picture of how the world really is. We need it to help us understand the world better – to identify and solve problems. So it’s so dangerous when data is used to skew the world around us.

“Having a huge amount of Instagram likes implies that people like the content, but that's not true when the followers have been paid, or are bots, or have lots of money pushing a marketing campaign behind them. And it makes people feel bad about themselves, but it's not an accurate reflection of reality. And it also shouldn't matter, because our obsession with quantifying our lives to measure happiness or success (in ways we never did before) puts us at risk of neglecting quality.”

Our obsession with quantifying our lives [...] puts us at risk of neglecting quality

Our Data as Culture art programme, curated by Julie Freeman and Hannah Redler Hawes, commissions artists and works that use data as an art material.

In its current exhibition entitled ‘😹 LMAO’ works have been selected for their playful yet critical approach to data and its uses. Irreverent, provocative, unconventional and plain silly, they ask us to challenge our preconceptions of data, and consider the humanity behind our technologies. Participating artists poke fun at the ineptitude of Google’s image search capabilities or the expectation that ‘big data’ will predict the future.

For me, the work that particularly stirs that same uncanny tension of comfort and self-awareness is Ceiling Cat, Franco and Eva Mattes’ physical Internet meme (not least because I sit directly underneath it).

The half-hidden real cat’s omnipresence ensures that we remember to reflect on both sides of the data story. As the artists say “It’s a taxidermy cat peeking through a hole in the ceiling, always watching you. It’s cute and scary at the same time, like the internet.”

For our Research and Development programme, we’ve been exploring multiple scenarios of imagined futures to help us understand how we move towards a world where people, organisations and communities use data to make better decisions, and are protected against any of its harmful impacts. Some of these are pretty dystopian, with a view to stimulating discussion and debate about where we’d like to get to.

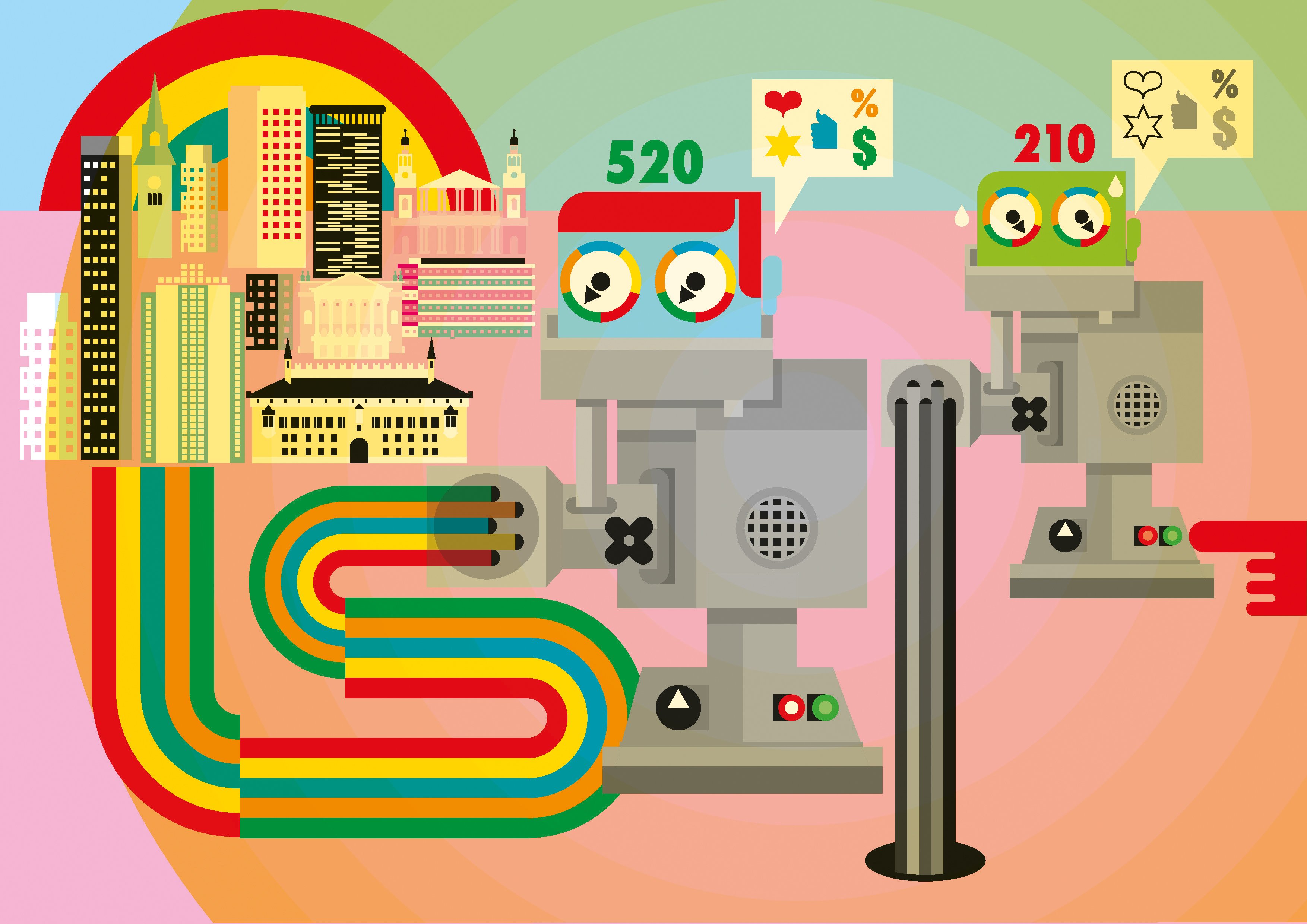

One of these imagined futures is a reputation barometer: a service that measures and monitors an individual’s standing by giving an overall score for their reputation. This reputation score would be informed by behaviour in renting or letting properties on peer-to-peer accommodation platforms. It could be used by other users of the platform or services outside the sector to make decisions about whether and how to interact with that person.We explored how the reputation could be represented, for example as a whole number on a scale that ranges from 0 – 600. This ‘score’ is assigned to an individual through the assessment of a number of data points, building a picture of an individual’s trustworthiness.

Image: An illustration we commissioned from design collective Du.st to portray the Reputation Barometer potential future.

If you’re reminded of the ‘Nosedive’ episode of Black Mirror – where people can rate each other for every interaction they have, impacting their socioeconomic status – I’m with you.

We will be exploring some of these concepts, and related issues of how we measure progress towards diversity and fair representation, at our ODI Summit in November this year.

The theme of the summit is around ‘data and value’ – how we can create value (whether economic, social or environmental) with data, as well as embed our values within data.

Along with equity and fairness in broadening data’s benefits for society, we will look at how we can improve trust in data and tech, and how to be ethical as well as innovative. We’ll also be asking how and why we measure diversity. What are the unintended consequences that can come with particular methods, and how can they be worked on? How can the insights we gain, either as organisations, governments or communities, be communicated and acted upon constructively? How can we quantify people while respecting their individuality, community, and equality?

We’re keen to hear your ideas for people and concepts to include. Please share any you have with us at [email protected], and feel free to tweet me at @anna_d_scott.