Peter Wells explores how investment in data infrastructure can help to address current UK transport challenges and unlock the next generation of transport jobs and services

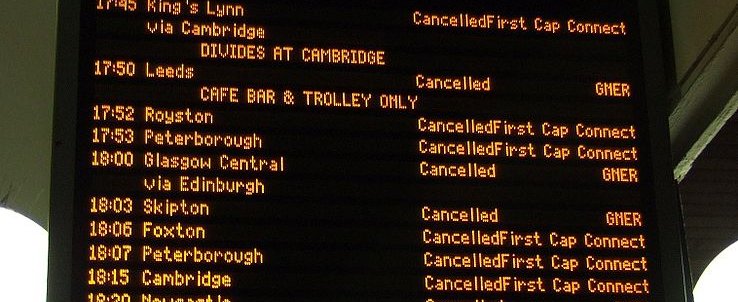

Transport is in crisis in the north of England. Cancelled, overcrowded and slow trains cause misery for millions of people. Both central and local governments agree that we need greater investment in, and local control over, transport services and infrastructure.

But we need more than physical transport infrastructure. Investment in data infrastructure (invisible but vital) is also needed to both solve the current problems and unlock the next generation of transport jobs and services.

UK transport industry challenges

Currently in the UK we lack access to good quality data about: national transport investment; the availability and capacity of transport services; the volume of desired and actual passenger journeys; congestion on roads; and even the price of bus journeys and which company offers them.

We need access to robust data to make good decisions – ranging from which route to take to work, through to public sector decisions about where and how to target investment.

Transport companies are not sharing data effectively which has a detrimental impact on services. People who want to travel, whether it be from one side of Manchester to another or a longer trip from Newcastle to Blackpool, struggle to find the quickest and most cost-effective route. If they choose to travel by public transport then they want to buy a single ticket regardless of whether this involves a combination of metro, train, bus or taxi. They just want to get from A to B.

In our 2017 paper, the case for government involvement to incentivise data sharing in the UK intelligent mobility sector, co-authored with Deloitte and the Transport Systems Catapult, we found that organisations weren't sharing the necessary data to enable effective, joined-up services. We reported that unless action was taken then by 2025 the UK would lose £15bn of potential benefits. Some of this action could be taken by individual companies but others needed public sector support.

We also explored the ‘human elements’ of sharing transport data in our report Personal data in transport: exploring a framework for the future. We found that alongside inspiring innovation and the creation of better services, data sharing highlights the need for organisations to address critical questions of trust, ethics, equity and engagement in how data is used. This will become increasingly important as people grow more aware of data issues and as they gain more control over data about them.

Meanwhile, other countries are taking steps forward:

- France is at the forefront of driverless metro technology as detailed in our report Transport data in the UK and France.

- In the USA and China governments and companies are investing heavily in driverless cars with trials taking place in multiple cities.

- The Ethics Committee of the German Federal Transport Ministry, with its own strong car industry, has published a code on automating driving describing the role of data, and providing guidance on vehicle behaviour.

- New York’s Taxi and Limousine Commission has introduced rules requiring rideshare companies, like Uber and Lyft, to share detailed data about their journeys so that it can improve road planning.

The UK is currently behind the curve on realising the benefits of data in transport, and alongside the poor service provision, we risk missing out on the next generation of jobs and the tax revenue that comes with them.

Tackling these challenges requires investment in data infrastructure

Data is an emerging, if invisible, form of infrastructure that every sector of the economy relies on. Good infrastructure is there when we need it but, at the moment, too much of our data infrastructure is unreliable, inaccessible, siloed or is not freely available. Data innovators struggle to get hold of data and to work out how they can best use it, while individuals do not feel that they are in control of how data about them is used or shared.

Without a reliable, maintained and far-reaching rail and road network, the ability of individuals and businesses to move around is restricted, communities become isolated, and the transfer of knowledge and ideas becomes difficult. It is the same with a restricted data infrastructure: innovation is restricted; services become biased around pockets of information; and communities can remain unrepresented.

Open data is the foundation of this emerging vital infrastructure. Much of the data that helps with our public debates – such as the information about spend and congestion that helps us make investment decisions, and our personal decisions, such as the price of a bus journey – should be open for all of us to use.

To realise these benefits, this we need private sector transport providers, central government and local transport authorities to open up more data.

For over 10 years, Transport for London has been openly publishing data (timetables, service status and disruption information), driving operational efficiencies, increasing use of the service and generating £130m of economic benefits in job creation and faster journeys. To encourage similar initiatives across the UK will need more involvement from private sector transport providers who are more dominant outside London. The benefits should be clear but if private sector providers cannot see them then it may need government to intervene, either directly or by giving more powers to local regulators.

Other parts of data infrastructure need a different kind of investment. Open standards for data describes not just the format of data but also the rules by which it can be shared, and who with. We need the sector to work together to create better standards for transport data. Those standards might describe how personal data can be collected, shared and used. They should be accompanied with guidelines on the ethical questions to be asked and publicly debated as new services are being designed and built.

Accompanying both open data and open standards for shared data is the need to invest in data governance. Governance to help align investment in data infrastructure with what people need, to ensure that data is made available in a way that creates equitable outcomes, and to help ensure that data is not misused. We are all still working out at what level - city, sector, national and global - this data governance is needed, but the UK's existing transport regulators, like many other regulators, are generally unfamiliar with this type of data governance work and will need more skills if they are to take on the role.

It is investments and interventions like this that will tackle the data challenges that we identified in our reports and help both create new jobs and improve our transport services.

The north led the way on transport in the Industrial Revolution, can it do the same again?

Investing in data infrastructure alongside physical transport infrastructure is essential in the 21st century. It can:

- unlock innovation.

- create a share in what the Transport Systems Catapult estimates to be a £900bn industry by 2025.

- help to create better services, such as buying a single ticket, regardless of how many transport providers we use on a journey.

- create more trust in new technologies like ride sharing services and driverless cars.

- help us to make better transport investment decisions.

This requires a brave and fearless approach. Citizens want and deserve better services but many citizens are also fearful of data issues. Companies also instinctively want to keep data to themselves and are are often uneasy about making data more accessible.

We need to be open with data and open minded to ideas; to win over passengers’ trust; to give them more control over and access to data; and look to a future where complaining about delayed trains and badly scheduled buses is no longer a British pastime.

When George Stephenson was designing and building The Rocket in Newcastle in 1829, he was helping launch a new era of transport services – the railway – but he was also building on the innovations of previous generations. The Rocket was tested on tracks that had been built for horse-drawn wagons carrying coal from mines to ships. The railways amplified the benefits of the Industrial Revolution, led to a wave of change that improved people's lives, connected cities together and led to massive job creation in the north of England.

We are now living through a similar wave of change created by the invention of computers, the internet and the web. The north needs greater investment in transport infrastructure but this won't deliver all of the potential benefits. Can the north repeat its 19th century trick in the 21st century, but this time by investing in data infrastructure alongside its transport infrastructure?

Whether you're a transport business, a transport regulator or the inventor of the next Rocket if you want help with tackling your own transport data challenges then get in touch with the ODI at [email protected]

First published on Transport-Network.co.uk