Has the UK's Department for Health and Social Care acted outside its authority by partnering with Amazon? What does this mean for future contracts between the NHS and big tech? The ODI’s CEO Jeni Tennison shares her interpretation and views on this recent controversial partnership

Earlier in the year, the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC) entered into a partnership that lets Amazon have access to DHSC information. A poorly worded and partially redacted contract between the DHSC and Amazon has increased concerns about their partnership. Now lawyer and campaigner Jolyon Maugham has filed a formal complaint about the DHSC to the European Commission, claiming it has broken state aid rules. How has it come to this?

The explanation for the partnership was that it would mean Amazon’s Alexa voice assistant – available through its Echo and Dot devices and others – would be able to use NHS website content to provide accurate information to people asking about illnesses and symptoms. Voice assistants aren't just growing in popularity generally: some people may rely on them, for example because of a physical impairment, so ensuring they provide accurate information is important.

NHS website content is high-quality evidence-based information, overseen by the NHS’s Clinical Information Advisory Group, about conditions, treatments and medicines, tailored for a UK audience. It's better for people to rely on this information than non-authoritative information that happens to be top of a search result or information written for people in the US who have a different healthcare system. If people use Alexa or other applications to access information about diseases, conditions and treatments, this is the information they should be given. It’s already public and it’s already used by 1,500 other companies according to NHS Digital.

How do companies usually get access to government data?

Information on the NHS website is generally open, and available for anyone to access, use and share under the Open Government Licence (OGL). What does that mean? Well, anyone who wants to use information that someone else owns (has copyright or database rights over) has to have permission. That permission is described in a licence. The OGL is the standard open licence used for all sorts of non-personal Crown copyright information (information created by the government).

The most relevant piece of legislation governing this is the Re-Use of Public Sector Information Regulations 2015 which (with some exceptions and caveats) says public bodies should make public sector information available free of charge to everyone under the same terms. The National Archives manages the UK Government Licensing Framework which states that Crown copyright information and data must be licensed under the OGL unless public bodies have a delegation of authority to use a different licence.

In some cases, public sector bodies add terms and conditions around the use of application programming interfaces (APIs) they offer. There are various reasons for this. Some are based around concerns about misuse of data or a desire to be able to track who is using the data. For example, sometimes organisations add terms and conditions to API access while the content itself is licensed as OGL. These can require data users to register, or to not use data in misleading ways, or to always use up-to-date information. These conditions are born out of concern to ensure public sector information is handled properly by organisations who reuse it.

The information that is open on the NHS website is also available through a syndication API. That API has additional terms. These terms constrain, for example, the way organisations that use content from the NHS represent the fact that it’s official information, the fact they have to keep it up to date, as well as technical things like how many requests applications can make on the API within a given time period.

How has Amazon got access to this government data?

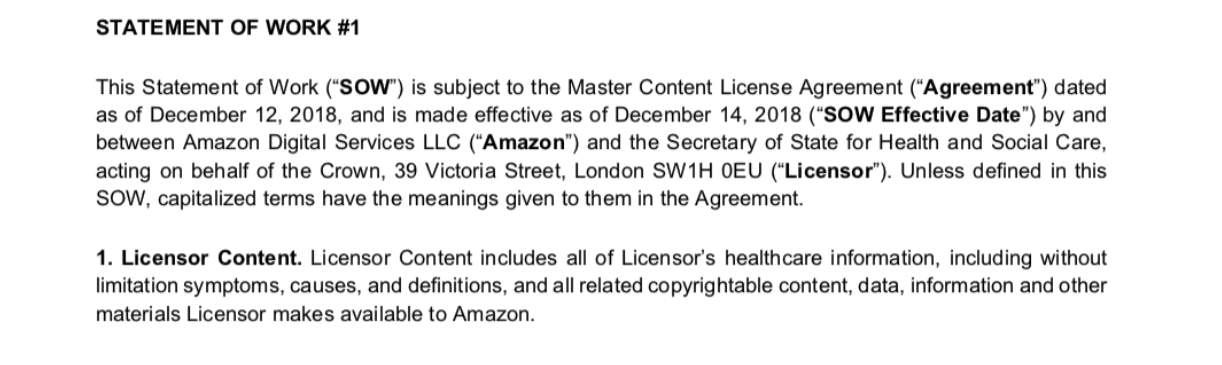

When the DHSC formed its partnership with Amazon, it created a separate contract to cover the use of this information. Reportedly, it adapted and adopted a standard licence agreement that Amazon uses when accessing data from other sources. I assume this is because having consistency in their contracts for accessing data reduces both work and risk for them. Thanks to medConfidential and Privacy International, this contract has now been published. It is redacted in some places which means no one outside the DHSC or Amazon knows everything it says. The DHSC, which did the redactions, says the redactions are there to protect Amazon's commercial interests.

The fact that this separate contract exists, the fact it's redacted, and the wording of some parts of the contract, lead to confusion, distrust and concern. This is heightened by the fact that it's health-related data; that there is a general distrust of big tech like Amazon and what they do with data; and that there's a touch of flame fanning by campaigners who rightly want to hold government to account around how it collects, uses and shares data, especially with big tech.

I'm going to try to unpick the concerns I've heard.

Problems with how we talk about licensing

When I spoke to people at the TechUK Digital Ethics Summit on Wednesday about what was going on, several people thought the contract was actually transferring copyright and database rights to Amazon. Using ownership language like "giving away" can create this impression.

That is not what the contract does. Data and other information is not like a house or car. More than one organisation can have a copy of it and use it at a time; when a new organisation starts using it, that doesn’t stop another organisation from using it too (data is non-rivalrous). When you license data to someone, you’re just saying they can use it: that doesn’t mean they then own it. For example, it doesn’t mean they can stop other organisations from using it or stop you from sharing it with other organisations.

Problems with the contract

I should note again that we don't know everything the contract says because some of it has been redacted. In its response to medConfidential’s FOI request, the DHSC say it redacted information that weren’t related to personal data. It could be that some redactions include constraints on what Amazon can do with the information, that have been redacted because the DHSC are concerned that revealing concessions they won from Amazon would damage Amazon's position in future negotiations. It could be that they cover details that the DHSC is concerned about the public being aware of, because it is worried about the reaction of it were they known.

Whatever is behind the redactions, obscuring details fuels distrust. Both the DHSC and Amazon should be concerned about their reputation around how they handle data, and be motivated towards transparency around their arrangement. It would be much better for everyone if Amazon and the DHSC are being held to account on the full facts rather than on the basis of speculation. A report from the Open Contracting Partnership on confidentiality in public contracting busts 10 myths around commercial confidentiality and recommends both minimising and explaining the reason for any redactions. The DHSC should have followed these guidelines, and ideally published the contract in full.

What we can see of the contract is unfortunately worded in ways that again fuel distrust. Most significant is the way in which the licensed material is defined:

From his interview with the Daily Mail, Jolyon Maugham has pulled out the phrase "all of the NHS’s healthcare information". Using that phrase naturally makes people think it covers personal health records. But the Licensor is not the NHS, it’s the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. From the background provided by the DHSC and the remit of the DHSC in the management of healthcare information (individual health records are managed by the NHS, not DHSC), it’s clear health records are not within the remit of the contract. But it is not surprising that people draw that conclusion given their underlying levels of concern about the way data about them is handled by both government and big tech.

Custom agreements are problematic for a number of reasons. The biggest in this case is that it claims to license Crown copyright information and the DHSC is not on the list of organisations that have a delegation of authority to do that under anything but OGL. The DHSC appears to have acted outside its authority in granting a licence to Amazon for this material. (In fact there are also licensing terms in the standard agreement they don't have authority to give.)

The non-discrimination regulation in the Re-use of Public Sector Information Regulations 2015 indicates that all organisations should have access under the same terms. We should be able to tell if the terms in this contract are equivalent to those offered to other organisations in the standard agreement. I also think that taking a contract template from the prospective user of data, rather than dictating those terms, is avoiding one of your essential responsibilities as a data steward. The government should be licensing data under its own, consistent, terms, not adapting them to those needed by licensees.

Problems with sharing data with big tech

Putting the details of the contract aside, people have concerns about Amazon having free access to non-personal public sector data, given its dominant market position and questions about how much tax it pays in the UK.

I have written about this previously. The concerns are reasonable: it is true that when data is made available on the same terms to everyone, those who have more resources, capability and existing access to data (like big tech) will benefit most from it. It is also true that open licensing of information means if an organisation builds a service using the data, and makes a profit from that service, they get to keep that profit. In an equitable world, those profits would be taxed and the public would get an indirect return for the data they have provided. In the context of an ineffective tax regime, that doesn't happen.

Jolyon Maugham is saying the government is breaking state aid rules in this case because Amazon is benefiting from the data being freely available to them – by more than €200,000 (£168,600) – and over the three-year limit placed on these benefits. To be state aid, it also has to give an advantage to one or more undertakings over others, distort competition, and affect trade between member states. It will be interesting to see how that value is evidenced, how those arguments play out around the provision of access to data which is also freely available to others, and how this interacts with the European Commission’s longstanding policy drive to open up public sector information for transparency and to stimulate invocation and economic growth.

Since fixing taxation of multinational tech organisations is difficult, people tend to concentrate on the remedy of charging larger organisations for access to data. Unfortunately when it comes to data, this can be counterproductive: it limits the ability for people to join data together in ways that can unlock social and economic benefits, and it disproportionately disadvantages smaller organisations who cannot afford the legal fees required to navigate complex licence agreements, or the insurance fees required to protect them from legal action. Opening data advantages big tech but restricting it advantages them more.

We can do other things to help the benefits of open public sector information be distributed more fairly, like providing training and investing in smaller organisations to help them build things. But I do not believe the problems of the dominance of big tech will be fixed by making them pay for access to this type of public sector reference data.

Problems with Alexa knowing our health conditions

The final set of concerns people have are about Amazon gathering data about us from our interactions with Alexa. Digital services gather data about us as we interact with them all the time. Google knows a lot about us from our search terms, Twitter from our tweets. Our behavioural data gives companies who provide us with services all sorts of insights into what we care about and what’s going on in our lives.

The concern here, then, is that when you ask Alexa "what are the symptoms of depression?" you are revealing sensitive personal information about yourself – that you may have depression – to Amazon, with little control over how it uses it. These concerns linger despite Amazon's assurances that it does not build customer health profiles or use health-related queries for marketing.

This personal data is in theory covered by the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and those existing protections and regulations enforced by the Information Commissioner’s Office. Amazon should have your informed consent to collect, use or share it and does provide mechanisms for you to delete it. But most people using Alexa will not have actually read through the T&Cs or thought through the potential consequences. In addition, Alexa is frequently used in contexts where it is used by people other than those who have provided consent: children and other family members, guests and visitors to people's homes. In this situation, the concept of informed consent is complicated.

Now, Amazon does not need to have access to any personal health information from the NHS (or indeed any information!) to do any of this kind of data collection. The DHSC holds that the relationship between an individual and Amazon is not the DHSC’s concern. But privacy campaigners are concerned that the partnership between the DHSC and Amazon – which leads to Alexa providing high-quality, authoritative, NHS-approved health information – might encourage people to turn to Alexa for help around their health conditions, thus increasing their reliance on it and enticing them to give away more information about themselves to Amazon.

The fundamental question here is how much responsibility should the data provider take for the way in which that data is used, and the consequences of that use? Open data publishers do not aim to constrain how that data is used. But there is a growing movement within the software development community to introduce ‘ethical licences’: licences which introduce conditions on the way in which code or software can be used or reused, such as not being used by companies that have unethical working practices. These licences are problematic (from an open perspective) because they create friction, uncertainty and incompatibilities. When openly licensed images of faces were used to create a machine-learning dataset, CreativeCommons highlighted that “CC licenses were designed to address a specific constraint, which they do very well: unlocking restrictive copyright. But copyright is not a good tool to protect individual privacy, to address research ethics in AI development, or to regulate the use of surveillance tools employed online”.

That said, if you are an organisation that is introducing additional terms and conditions around the use of data anyway, why not introduce one that asserts additional limitations? The DHSC could have added a clause to the contract with Amazon that required it to delete any recordings of requests that resulted in it providing information covered by the agreement, for example, or that required it to gain additional consent to keep data about health queries.

Conditions like these would require a monitoring and enforcement regime. Regardless of whether responsible use of revealed health information is required by GDPR or by contract, we need additional transparency about the way Amazon uses that information, and mechanisms for it to be held accountable for any breaches of its duties and agreements.

Conclusion

This case is a fascinating example of the complex set of issues that arise – around the reuse of public sector information, open licensing, competition policy, digital rights, and the value of data – when data is shared. Perhaps the most important lesson is that a lack of transparency around access to data fuels suspicion and distrust. There should be no surprises.

It also highlights how complicated deals around data can be. Understanding and explaining the complexity is hard, and it is easy to use terms that exaggerate people’s fears, in a way that obscures the very real things we should be concerned about. It is also easy for government officials to make mistakes and overstep their authority.

Issues around privacy and digital rights are absolutely crucial, and we have to continue to hold government to account on how it shares personal data.

But not all data is personal data. Non-personal data, like that about diseases and treatments, can inform and enlighten. It is much better for us to be able to rely on authoritative data than on whatever happens to rise to the top of search results. Lowering barriers to the use of that data helps us all. We need to be able to talk about these benefits as well as the risks and harms.

Now the pre-election period is over, I hope NHSX or the DHSC will act quickly to publish a less redacted, and preferably completely open, version of the contract. Hopefully they will make it clear Crown copyright information is licensed under OGL, avoid custom agreements and be more proactive and transparent about any contracts they do make in the future. But larger questions about how the benefits from data are equitably shared, and the responsibilities of data stewards over services that use the data they provide, will rumble for some time.