We’re constantly asked to make decisions about personal data about us, and we are only just starting to grasp the impact these decisions have on us, and others.

Here, Renate Samson, Anna Scott and Peter Wells share findings from research published today, on how ‘the people’ understand data, and a tool we’ve created to help us all have more nuanced, constructive discussions about data about us

Today we have published findings and creative outputs from a project exploring data rights, which we have worked on alongside the RSA and Luminate.

Running workshops and focus groups with members of the UK public, our aim was to understand what people understand and feel about data that is about them, and the rights and responsibilities they felt should exist around it. We also wanted to explore narratives that inform and engage people, enable more nuanced discussions and help people articulate their feelings about data about them.

Our outputs include a report, ‘About Data About Us’, a printed summary report and a short, shareable animated video, which brings to life some of the perspectives we heard and invites people to share their views with the hashtag #WeAreNotRobots.

Film by 2zero3zero, produced by the RSA with the ODI and Luminate

Our findings won’t be reflected as big but short-lived headlines announcing a definitive view of how the public feel. They can’t, because it couldn’t properly reflect the complexities and nuances that shape how data impacts our lives.

Our digital lives are complex

Never before has data played such an integral and granular role in how we live. On a daily basis, we are asked to make decisions about personal data about us – consenting to it being gathered and used for many purposes.

We are only just starting to grasp the impact that these decisions have on us, and others. We must think differently about data, and the rights and responsibilities around it.

As we explained in a blogpost a few months back, many reports have undermined people’s awareness of data, reductively concluding that people ‘don’t understand’ it, or don't care as long so they can get a benefit or offer. Some have gone as far as saying that ‘the public’ are resigned to data being used in ways they can’t change.

‘The public’ are often undermined as being ignorant

Our work shows that people generally do understand and care much more than they have been given credit for.

It has also highlighted the obvious but oft-forgotten truth that people are different, and that broad statements on what ‘the public’ know, or like, or want are fundamentally meaningless (something well-captured in Ollie’s “Not all people are the same…” rant in response to his fellow civil servant Glenn undermining the usefulness of focus groups in the satirical political comedy, The Thick of It).

Naturally then, people’s levels of understanding and feelings about data differ. Some are cautious about how data about them is used. Others are willing to share access to data about them liberally. Some want to understand all the implications of data protection legislation, others prefer to tap into what matters to them.

This is an important point to make. While data protection has progressed significantly with last year’s launch of the General Data Protection Regulations, other areas of policy, regulation and legislation is increasingly urgent across areas from data protection, misinformation and online harms, to competition, anti-trust and investigations into the impacts of how adverts are served to us. When making these interventions, governments need to listen to and cater for people’s different views.

Our work is just one contribution to the wider debate around data rights, but what it showed was that in spite of people’s difference, what many people do have in common is that they care about their data rights and the responsibilities around them. Many people we spoke to said they enjoyed the benefits that technology has brought them, but are concerned about how data about them is used.

Most people told us that they make choices and decisions based on how they feel at a moment in time and that they want to be able to change their minds when they feel differently. Many said they didn’t like feeling categorised by machine-learning algorithms, because it undermines this important and critical sense of personal agency.

We heard a range of ideas about how people could be better engaged, from alerts that make it 100% clear when data is being collected to improvements in how we can opt out, better-explained cookies to ‘a dial’ that would let people make more nuanced decisions about what they share and when.

Experts may dismiss these things as impossible or naive, but that’s not the point.

The point is that members of the public have ideas and want to be involved. They want to be talked with and listen to, and for their views to help shape how policies or services are developed.

Data about us: we need more nuanced discussions

While this work shows a general levelling up of awareness and understanding (particularly around data protection), there is still important work to be done.

We found that when people said they were angry or concerned by data about them being shared, they struggled to say what data they were worried about most, or what data they might not mind sharing. Often, because they didn’t know the difference between data about them that is sensitive from, say, data about them that is anonymised and shared for society.

Data about us comes in many different guises and can have a range of different impacts, not all always about the individual, but often about society as a whole.

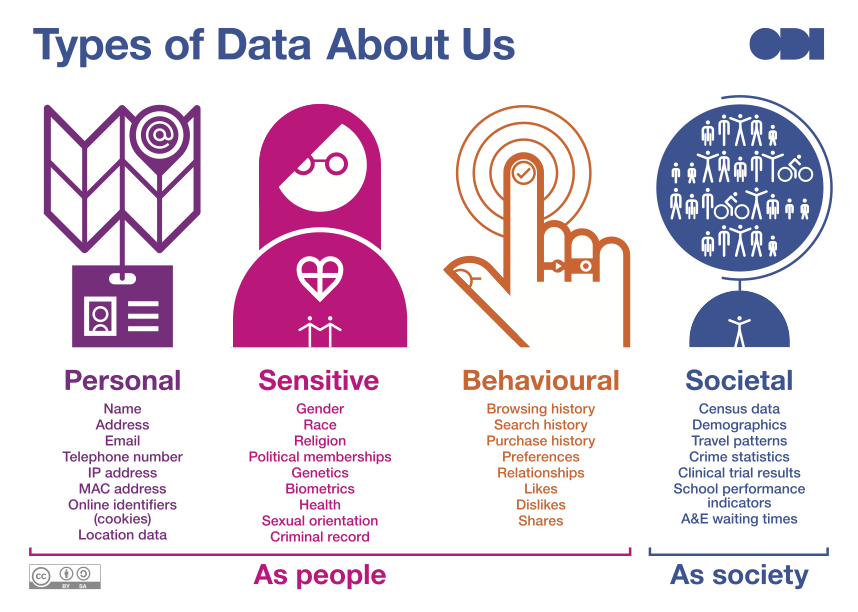

In light of this, we created a graphic tool to help define the different types of data about us: personal, sensitive, behavioural and societal.

This graphic is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

When we tested this graphic with participants, we found that the conversations became more nuanced. It helped people to more clearly and articulately tell us when they were happy to share and why, and what communication, transparency and engagement they’d expect from government and organisations about this. As our ODI Manifesto says: "everyone must have the opportunity to understand how data can be and is being used" and "everyone must be able to take part in making data work for us all".

We hope this work is another step towards making that manifesto a reality. We hope it will help to start a conversation between people, governments and businesses, along with NGOs, interest groups and think-tanks.

We will be discussing our findings at both the Labour and Conservative party conferences in the UK. We will also be presenting the work at MyData in Helsinki next week, and then we intend to take the work to France and Germany to hear some international perspectives.

Share your views and follow the conversation with #WeAreNotRobots.