This is the first in a three-part series on critical data infrastructure as part of a project: Power and Diplomacy in Data Ecosystems. These three initial provocations demonstrate how we have begun to explore topics related to international data ecosystems, physical infrastructure and dynamics of power. All three provocations will be probed and challenged through a workshop with key researchers and through a joint project with the Data as Culture programme.

Clouds and wires

The cloud, wifi, data. There is a tendency for their invisibility to lead to complacency. The cloud in particular – it is nebulous, it is natural, where is it? It’s everywhere!

Obviously, we know this can’t be true. We know the cloud refers to physical servers that are accessed over the internet, and the software and databases that run on those servers. The cloud and the internet are too big to comprehend fully. The internet can be considered to be a hyperobject, a term Timothy Morton describes as ‘entities of such vast temporal and spatial dimensions that they defeat traditional ideas about what a thing is in the first place’.

The most commonly attributed hyperobject is climate change. Why does it matter that the internet is a hyperobject? While the scale of the internet is hard to comprehend, yet the physical manifestations of it can be touched, seen and analysed.

Materiality of technology

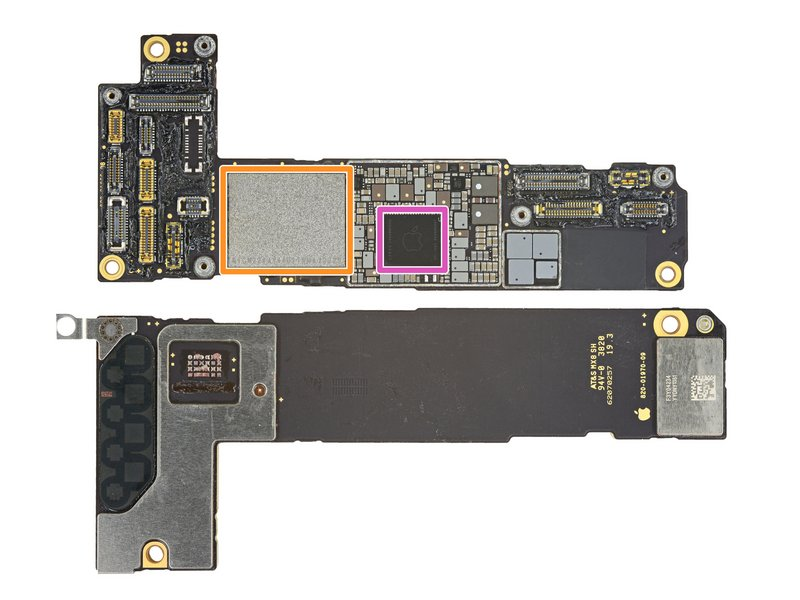

To function in a largely wireless manner for the user, the internet needs physical infrastructure – data centres, satellites, undersea cables, physical devices, routers – to operate. These pieces of physical infrastructure are central to our economy, but they are often unthought of by users. Where are they located? What local regulations are they party to? Where are the parts manufactured? What are the environmental implications of their operation? How are the sites kept physically and digitally secure? Who maintains them – private companies, governments, a mixture? To mirror the academic Castells, there is a paradox at the centre of our modern, digitised lives; that as we further shift towards a wireless world, we are tied further to the physical infrastructure that underpins it. Data centres are the most direct physical manifestation of our data economy. Every byte and pixel that forms our digital existence – the texts we send, the pictures we take, the music we stream – must be stored somewhere physical and material. Our phones, computers, cameras and TVs tend to have physical storage located within them (as shown in orange on the diagram below).

This scales massively when we start to think about all of the data that is not stored on our individual devices – think about the web pages you visit, the software you use, or your companies’ data. This leads us to data centres, specific buildings designed to warehouse all of this data.

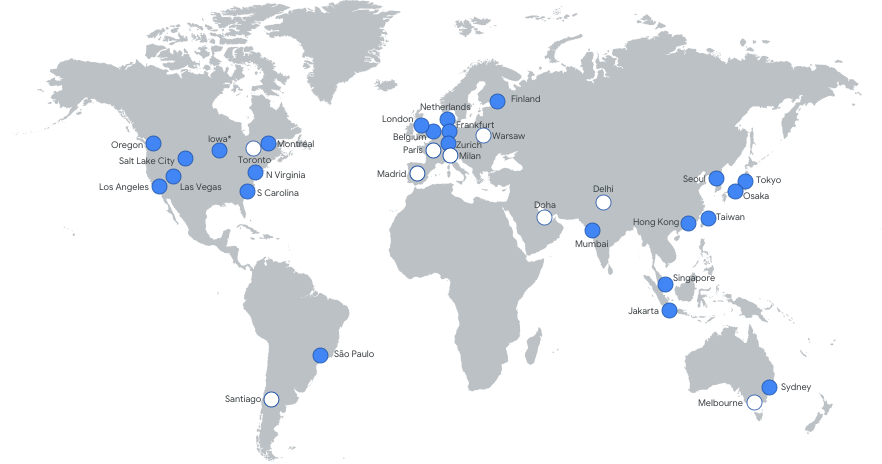

Now, where these monolithic centres are located is not an accident, but instead sites are carefully selected based on a number of considerations, which, depending on context, may include:

- Data centres need stability and sturdy geology, away from earthquake zones.

- Political stability is also important. Data centres should not be located in places of conflict or turbulence.

- Data centres generate significant heat and therefore it makes sense to build them in places with a stable (preferably colder) climate, hence a cluster in Scandinavia and in the dry-air of California.

- When a data centre in a different country to where the data is accessed, it is important that there is regulation which facilitates cross-border data flows is preferable. This will become more contentious as countries push forward with data localisation approaches despite no actual security benefits in doing so.

- Linked to this is proximity to users. Here is a real concern that locating a data centre too far away from users’ geographical location will lead to network latency issues and result in buffering and increased load times. International stock markets can become victims of latency, for example the closer geographically a data centre is to a financial exchange, the sooner it gets information on stocks. Getting information milliseconds earlier might not seem remotely important, but with automated trading it can distort the market.

- And finally, data centres should make economic sense. Data centres can often be found in locations that were previously centres of industry and manufacturing due to the existing infrastructure. Companies may be offered incentives such as tax breaks or energy discounts to attract data centres.

Each coloured dot above represents a single Google data centre complex. Now add in every other data centre for companies such as Amazon Web Services and more and you start to get a better picture of the scale and geographical spread. On this scale, data centres become objects of territorial reach as sites, infrastructure and labour are paid for by multinational companies while straddling both regulatory jurisdictions.

These choices are not politically neutral; as data becomes more pervasive it intersects more deeply with other discourses.

For example, the overturning of Roe v Wade upended decades of legal protections for reproductive rights. In many states it became illegal to access abortion care and potentially even to be an abortion-seeker. This inter-connects with data studies as much of this interaction now takes place digitally, mediated through apps such as Proov and Clue.

In 2018, search history data was used in an attempt to charge a woman for an at-home pregnancy loss. Data has already been used to prosecute people who seek information about abortion services. These technology providers would be party to this anti-abortion regulation and many representatives feared that ‘police will obtain warrants for customers' search history, geolocation and other information indicating plans to terminate a pregnancy.’

If these data centres and company headquarters are located in rights-friendly states such as Vermont, Michigan or California then there would be greater protection granted for data rights. For example, Proov is considering moving its ‘data center locations away from state governments unfriendly to abortion rights as possible’. This connects ideas of data to physical infrastructure to contemporary rights issues, demonstrating the interconnectedness of data infrastructure to modern society.

From the cloud to the ground

The environmental cost of data consumption is a bit of a sticky subject in the data world. Data centres lie at the heart of the Castells paradox above – everything digitally has a material cost and one of the biggest material costs is the energy consumption at data centres.

As tech companies wash their reputations with green initiatives, they are powering economies of burning and extraction. From the green ‘AI for climate crisis’ startups to the Shells and Chevrons of this world, they all need mass computing power for their research and business models. This computing power requires servers, and these servers need power.

Data centres contribute to the national energy consumption of their host nation, and therefore as countries strive to meet the bare minimum drops in consumption and emissions required to meet global standards, there will likely be a trend of thrusting these centres onto poorer nations. It wouldn’t be surprising in the next 10 years for there to be the data centre equivalent of trash island. An extensive MIT article draws the below conclusion:

- In North America, most data centers draw power from 'dirty' electricity grids, especially in Virginia’s 'data center alley', the site of 70 percent of the world’s internet traffic in 2019. To cool, the Cloud burns carbon, what Jeffrey Moro calls an 'elemental irony'.”In most data centers today, cooling accounts for greater than 40 percent of electricity usage

- The Cloud now has a greater carbon footprint than the airline industry. A single data center can consume the equivalent electricity of 50,000 homes. At 200 terawatt hours (TWh) annually, data centers collectively devour more energy than some nation-states.

Attempts to reimagine data centres into thermal urban infrastructure must be considered and accelerated should they be successful.

While many institutions operate their own smaller-scale data centres, for example universities or business, there is a continued shift to scale up and benefit from ‘hyperscale’ data centres, run by Amazon, Google and Microsoft. There is a sensible logic underpinning this. Some have argued that it can lead to a consumption decrease by up to 25% and can also make sense from a management and process-efficiency perspective. However, it is also a further consolidation of power and a monopolisation of the data cyberspace.

And not just power, data centres (along with all of our other technologies) require lithium and cobalt and more to make components such as processors and batteries. The mines that provide material for our technologies are connected to systemic human rights and labour abuses. These cloud infrastructures from above, directly require deep scars in the ground in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chile and Brazil.

Virtual to physical

The modern data world exists because of physical infrastructures, and the materials, labour and energy required to run them. This article exists as a prompt to always consider that everything digital and technologically is presently or historically connected to the ground somewhere.

Bibliography

To view connected research, see our collaborative bibliography – a curated, living repository of books, reports, podcasts and research papers compiling some of the brilliant work of researchers from around the world interested in how data and digital technologies shape new geopolitical dynamics worldwide.