Data portability is a new right in the EU GDPR legislation, yet most data is about multiple people. We've worked with IF to explore what this means for service designers and policymakers

By Peter Wells

We are very interested in data portability at the ODI. It is the bit of the EU General Data Protection Regulation that we think holds most promise to support innovation by giving people stronger rights around data.

We have already explored, and are helping countries and organisations deliver on, the potential of data portability in sectors like banking, telecoms, sharing economy and retail. It is one of the models which could increase access to data while retaining trust.

But if organisations implement portability badly it could damage trust. That would hinder innovation and reduce the benefits that data could create. It might harm people.

One of the challenges in the implementation of data portability is that most personal data is about multiple people. Our DNA, for example, reveals information about our parents, family and even our distant relatives. Utility bills reveal who we live with. Health records contain information about medical professionals as well as ourselves.

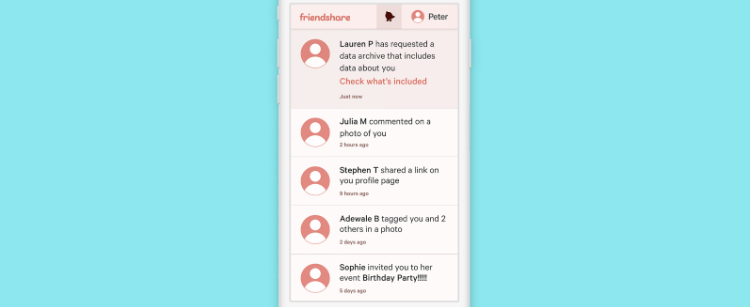

We recently worked with IF to explore the portability of data about multiple people. At the ODI, we like to develop our policy through a number of different activities, including prototyping. This project consisted of multiple rounds of identifying scenarios, prototyping potential services and showing them to citizens and consumers. We had a particular focus on the needs of service designers and policymakers to understand this topic.

The resulting research report, GDPR, data portability and data about multiple people, has just been published by IF. It has some fascinating findings. It shows the possibility of a whole class of new services that respect the rights of multiple people. But it also highlights the need for more work on this complex, and very human, topic.

Most people think data is just about them, yet some organisations know it is about multiple people

During the research, most people thought data was just about them and that they 'owned' it. This could be due to a number of factors such as individualism, the tone of current public debates about data, how we teach people about data, or the design of most current services.

The team found few existing services or design patterns that would help people understand that the data they were sharing or giving permission to third parties to use was also about other people. The services weren't taking advantage of what educational theorists call a teachable moment.

However, we know that some organisations understand that data is about multiple people.

This was starkly highlighted in the ongoing scandal about Facebook and Cambridge Analytica where a game used by some people revealed data about the friends and family they were connected to on Facebook. The collected data was then used to target political advertising. Meanwhile, the family connections in DNA were recently used by the US police to make an arrest in a murder case.

Social relationships affect people's behaviour around data, there can be tensions

People often interact with services that collect data as groups, rather than as individuals. Even if many people don't realise that the data is about multiple people then social relationships affect their behaviour. For example, people living in a shared household give control to an individual who is the account holder, while a parent might end up in control of the TV settings but be willing to give a child some control.

This shouldn't be a surprise. Our societies are built on networks of relationships between humans. We live, work and play together.

There can be tensions between competing rights, and a lack of a fair share of benefits. For example only the person managing the water bill in a shared household might benefit from building up the credit history that helps them get a mortgage, while two people might disagree over whether one of them can share the picture of another on a social media platform.

Better service design can help manage these issues, and lead to better services, but it will not solve them completely. Technology and data can only imperfectly model human relationships, and our shared and competing rights, beliefs and interests.

Often people need to talk with each other, and even then they might not agree.

We need to learn how to build services that manage data about multiple people

At the ODI we want people, organisations and communities to use data to make better decisions and be protected from any harmful impacts. Data portability holds great promise, it could help create a whole new class of services that improve people's lives. But if data portability does not respect the rights of multiple people then it could create harmful impacts. This will damage people and the organisations delivering services built on data portability. Facebook is the most high-profile current example.

The report recommends some principles for better design with data portability, but given technology's inability to completely model complex human relationships it is clear that while better design is required some of the necessary work cannot be done by individual organisations and services.

Tackling this challenge is likely to also require changes to how we teach people basic data literacy – or data literature – so that more people have a better understanding of data, along with the growth of institutions that help mediate when there are competing rights. If we see continued harmful impacts, and a market that fails to build services that respect people's rights, then we may need better regulation and legislation to ensure that we respect multiple people's rights.

Meanwhile, the possibilities provided by technology are constantly changing, as are people's needs and expectations. We shape technology, and technology shapes us. Different societies are moving at different velocities, and sometimes in diverging directions, as we adapt to the current information age. Our research took place in the UK, we might have had other findings elsewhere.

We need to learn how to build services that manage data about multiple people. Governments and businesses should lead by example in building better design patterns and exploring the other changes required. These are the organisations that hold most data and deliver most services. This work needs to take place in multiple societies and through service delivery as well as through classic policy.

If you want to work with the ODI to help you design better data services and policies, get in touch at [email protected].